By Bob Alvis, special to Aerotech News

Just the title “D-Day” gives most people the chills, when thinking of how much bravery and heroism took place on those shores and in the fields inland in France in June 1944.

American soldiers made their assault on Hitler’s Fortress Europe and its coastal defenses, devised by the best field marshal the Germans had in Irwin Rommel, and fortified by a well-trained German army. But as we discussed in Part One, when the Allies needed that close-up look at all the defenses and what would be waiting for the invading forces, that intelligence gathering would fall to a small group of specialized aircraft and their pilots, who most of the time were looking for some kind of respect.

When the recon pilots gathered on May 6 to begin those dicing missions along the coast of Normandy, I’m sure the chains of cigarettes and endless cups of coffee could not produce the calories that would be required to perform a task that many felt was a one-way trip. Adrenalin and American fighting-man bravado would help them define the word bravery in their own personal way.

The pilots gathered around a Lockheed Lightning designated an F-5, replete with nose art of Jane Russell from the iconic American movie The Outlaw. A young lieutenant named Albert Lanker, nicknamed “Louie”, from Petaluma, Calif., would settle into the cockpit and wonder about his fate as the very first “Photo Joe” who was going to try something that had never been done before, against the most heavily defended target in Europe.

During the run up to D-Day, the photo recon pilots would sleep on their planes waiting for the next mission.

Climbing into the cockpit of any aircraft, the pilot would have had uneasy feelings about what the future had in store for him. When you factor in the realization that he would be flying an aircraft with no way to defend itself, alone over enemy territory, 20 to 50 feet off the ground with no radio contact, all I can say is, the word “brave” seems a little inadequate. As the lone Lightning took to the air and crossed the coast at Dungeness, Lanker, with Jane Russell leading the way for good luck, nosed his craft down to 15 feet and through the ocean spray of the English Channel, made his way into the history books.

When Lanker arrived on the French coast at a location named Berg-Sur-Mer, he carefully made a circle around a rather large sand dune that seemed out of place. He then set his cameras to auto-feed, pushed his throttles up and at 375 knots and an altitude of 25 feet, made his speed run until the film ran out. Taking the enemy completely by surprise, Louie was amazed as he watched workers on the coastal defense obstacles scattering in all directions, as the crazed Lightning made its presence known to all those never expecting to see an Allied aircraft at 375 knots this up-close and personal. With cameras on the right and left and, on this particular plane, in the forward-facing nose, Louie kept his craft steady, making sure that his photo run would give the intelligence people information that could very well save hundreds of lives. At the end of his run, he turned inland and soared over the ridge of France that overlooked the beach, clearing it by just six feet. With a glance, he saw a young German soldier who stood in awe of this crazy American who’d almost clipped him with his wing!

When he set down at RAF Chalgrove, England, he watched proudly as the film was whisked from his plane and made its way off to the photo lab, to be passed off to bunkers below London where upper brass were eagerly awaiting the fruits of his dicing photo recon mission. So successful was this first mission, that two more were scheduled for the next day, on May 7.

The next day Lt. Fred Hayes and Capt. William Mitchell of the 31st and 35th Photo Reconnaissance squadrons departed together, then split up to cover different areas of beach. Mitchell covered the beaches from Dunkirk in France to Ostend in Belgium. Hayes was never heard from again and is thought to be a casualty of that flight 15 feet above a restless sea, just another American airman in an unmarked grave at the bottom of the English Channel.

But of all these heroes that were responsible for the saving of so many lives of the Allied invasion force on D-Day, there is one name that should be on the minds of every boy turned man who hit those shores.

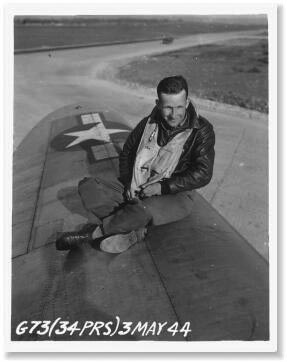

Garland A. York would be the one airman that history would look upon as the savior of D-day. Second Lt. York was the youngest photo recon pilot in the 34th PRS, and his photo run, performed on a day with very marginal weather conditions, would provide the most vital information the Allies had before the invasion. It was Garland who made the photo runs that covered the beaches from St. Vaast Dela Houge to Bancs Du Grande — the stretches of beach that would be known throughout history as Omaha and Utah Beaches.

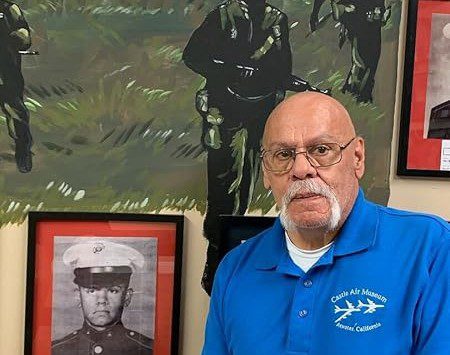

Courtesy photograph

There are so many more aspects to this often-overlooked aspect of D-Day, so many other stories of loss of life, and of the Germans realizing what the skimming Lockheed Lightnings were up to. They turned their fury on the lone pilots risking life and limb for a chance to help with the invasion of Europe, knowing full well that if death came it would be swift and brutal. Long after the war was over, General Eisenhower would be asked what was the greatest weapon he credited with the final success of the D-Day landings. He would without hesitation say the American Fighting Soldier — including a group of young pilots who, with little chance of success, gave us the intelligence we needed at great personal risk to claim that victory. So many men were heros on June 6 and beyond, but we must not forget that starting on May 6, the heroes of D-Day were already in action.

By the way, do you remember when I said that that when Lanker arrived at Berg-Sur-Mer, he saw that sand dune that looked out of place? Well when the film footage was developed, that strange sand dune was the keeper of a German 88 anti-aircraft and anti-tank artillery gun, and it was only by the act of total surprise that the Germans did not have the time to react to Louie’s arrival. If they had and Louie was lost, it could have changed the outcome of the D-Day landings.

For the 75th anniversary, we salute not only all the soldiers and sailors who made it a success at great personal sacrifice, but also the unknown Airmen who set the table for a German defeat.

Until next time, we remember and for now, it’s Bob out …