By Bob Alvis, special to Aerotech News

We are on the threshold of celebrating the 75th Anniversary of D-Day in a few weeks.

In modern society, we find the importance of remembering with certain bench mark dates, with the measurement of time in quarters. D-Day’s 75th will be the last of those special dates, for when we reach that June 6 date in 2044, the men who had a firsthand account of that historic day will all be gone. Only historians and families of that generation who know that grandpa or great-grandpa did something great will be left to tell the story of an amazing day, when the very best of the American spirit made a statement to the entire world that freedom would not be a casualty of an evil that had been unleashed upon the world.

Growing up in the Antelope Valley, we were no strangers to men who had a special connection to that day so many years ago. Personally, I knew a high school teacher, a friend who worked at Lancaster Community Hospital and an investment banker whose family was well rooted in Antelope Valley history, who had firsthand accounts of that day on the coast of France. They all came home from that war, some of the lucky ones who managed to find that path that made a return trip possible. Few people realize that if not for the heroics of a very close-knit group of airmen who pretty much go unheralded in the history books and in the media, the outcome of D-Day could have looked a whole lot different. Those three men I knew as friends and neighbors may have never made it home, along with thousands more, if the invasion of Normandy had taken a turn for the worse.

When Lockheed Burbank line workers were rolling P-38 Lightnings off their production lines, little did they know that a few of those airframes would go on to become what General Eisenhower, the supreme allied commander, would say after the war was the one reason that the invasions were a success, saving more lives than one could ever imagine.

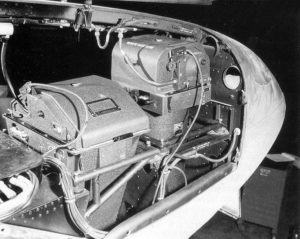

The variant of the P-38 that would prove to be the work horse of the pre-invasion was called the F-5 photo reconnaissance version. With skilled photo recon pilots standing by in England as part of the massive troop build-up, the wheels were put in motion to start getting a grip on what coastal defenses would be encountered when the first landing craft hit the beaches.

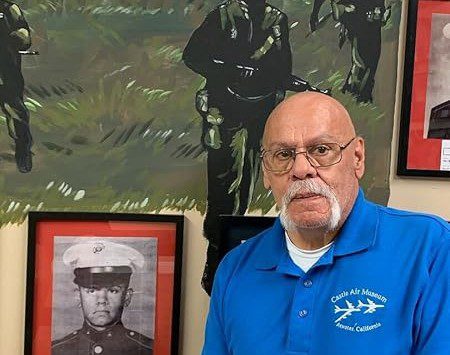

Photo recon pilots were a special breed, and always lived in the shadows of the fighter pilots and bomber pilots heroic gloss. “Photo pukes” was the nickname they were labeled with, and when the tales of airborne heroics were being told the Photo Joes were off by themselves, feeling pretty much like the orphans of the Army Air Corps. But for this special group of men, their missions were more dangerous then what the other pilots or the folks back home would ever realize.

Those Lockheed F-5 photo recon birds had no armament at all. In the nose of the aircraft was an array of cameras that could take photos and run film lengths of targets before bombing runs and after, along with troop movements and defensive positions of the enemy. When a Photo Joe took to the air, he was on his own with no radio contact, no escort, no guns to defend himself, and only his skill and speed to evade and enemy. A recon pilot was looked upon as a prized kill, as his mission represented the intelligence being gathered to inform and aid the nation he was tasked to defend. Lost intelligence from the battlefield could be the difference between winning a battle and losing it.

Prior to the planning of the D-Day invasions, most photo recon missions were being flown at high altitudes. Even though these missions and the intelligence they gathered were helpful to the campaign, the coastal defenses of Normandy would require a different tactic. Years of preparation by the German defenders had built a very formidable defense fortified with booby traps and perilous anti-invasion devises, along with well-hidden gun emplacements.

The high command put forth information requests to many different commands when it came to the June invasion. The one they listed as number four on their priority list was the close-up photo reconnaissance of the costal defenses all along the beaches of France, which needed to be obtained in a manner that would not tip off the German high command as to the Allies’ intentions.

When the orders reached the 34th Photo reconnaissance unit, the pilots knew they been handed a pretty dicey mission with a very low probability of survival. As the pilots sat through their first briefings, they were given an outline for practice missions. The pilots were all in agreement that the loss of life would be too great for just practice runs, and that flying the mission in full would have a better outcome and would actually be less dangerous. Command agreed, and dates were set for the beginning of the missions to find out the secrets of Hitler’s fortressed Europe.

Because of the danger, pilots were asked to volunteer. Before long, a handful of men stood at the ready to face an unknown, to create the models that would be key to Allied victory. These missions became known as the “Dicing Missions,” because survival was pretty much a roll of the dice.

As the first Lockheed Southern California-built F-5 got ready for that first mission on May 6, 1944, the pilot had been briefed that the best chance for survival was flying at an altitude of sea level to 50 feet. The time was at hand to “put up or shut up” and see what the men of the Army Air Corps photo reconnaissance units were made of.

In the next issue of High Desert Hangar Stories will put you in the cockpit for part two and you will fly along with the men who made history and became the silent heroes for thousands of men who hit the beaches on June 6, 1944.

Until then, Bob out …