One of the least-known stories of World War II is a program that was so radical it can leave the reader today wondering how such a program ever got approved — and more than that, how they ever found the pilots to fly it.

A bit of early history of World War II recalls that bombers flying over Europe in the opening rounds of bombing campaigns were getting a shellacking by enemy fighters. Gunners on the bombers were entering the combat arena without adequate training in air-to-air combat. Gunnery training in the United States was pretty static and didn’t do much to mimic actual combat conditions. Riding on flatbed trucks and shooting at targets with shotguns was the lead up to sitting in the back of an AT-6, shooting a tow target. All over the Southwest at Army airfields like Vegas, Kingman and Yuma, the young gunners did their best to take their training to the enemy — but the reality was when the planes started firing back and they were employing air combat maneuvers, they had to quickly adapt to combat in a hostile environment. The learning curve was harsh, and the losses of aircrews and planes all pointed to the lack of realistic training. All that stood between the Luftwaffe and total annihilation were these brave young airmen, who did their best to learn fast and give their planes a chance at survival. When the word started filtering back to the United States that better training was needed if we were to have a chance at victory, American technology started to come up with more realistic training, including film and electronics to try and create a more realistic combat simulation experience. Many looked like nothing more than arcade games, but at least it was an effort to try to do a better job of training our airmen.

Misgivings about the effectiveness of gunnery training extended all the way up to the highest echelons. Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, the Army Air Forces’ big boss, complained in a letter to Training Command that “reports are still being received which indicates a serious lack of gunnery training for our aerial gunners ….” Planners and instructors were trying, as attested by the constant changes in curricula and procedures, but frustrations continued to mount and combat personnel still did not live up to expectations.

In 1943 and 1944, the programs limped on. Only by sheer determination did the gunners manage to start making a dent in the enemy’s air forces, but something needed to change, as mission requirements would send the seasoned gunners home having flown up to 35 missions in the latter part of the war.

So begins the amazing story of Maj. Cameron D. Fairchild, who figured there must be a better way to train our gunners for combat. He began a quest that no Air Force reservist would ever attempt. He was zealous to a fault and so dedicated to his radical concept that he risked rebuke and worse, to see that his proposal received proper attention. Defying the traditions of ordnance development, Fairchild and two converts, Paul Gross and Marcus Hobbs of Duke University, embarked on a three-year struggle which eventually ended up being Operation Pinball.

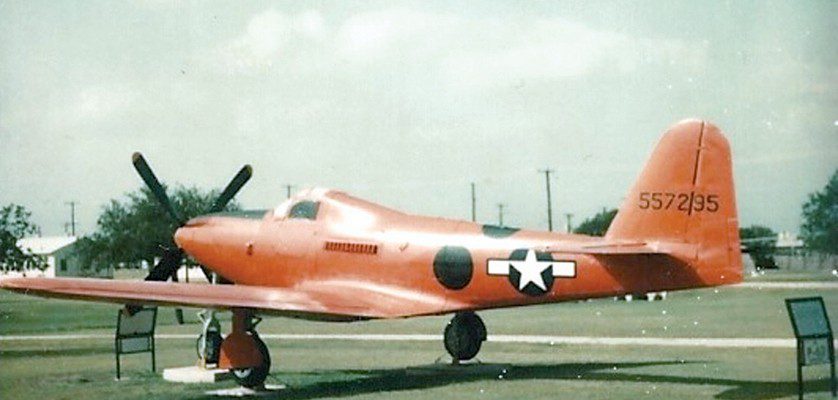

On the parade grounds at Lackland Air Force Base, Texas, stands a Bell RP-63G King Cobra. Painted in the standard colors of a silver warbird of World War II, the paint job does nothing to reflect on its mission that it flew in the last year of the war, along with 31 other Cobras. These planes, coupled with a miracle of bullets developed at Duke University, were a triumph of technology. The ceramic bullets manufactured by the Bakelite Corporation, also known as “frangible” bullets, were strong enough to be fired from machine guns at realistic velocities, but they shattered on impact with the aluminum armor on the planes.

The heavily armored Cobras were decked out with lights on the nose and wings that flashed when the plane was struck, making the plane look like a flying pinball machine when a good gunner was at the trigger. The plane was perfect for this role, as it was fast and light and could fly realistic fighter attacks, yet had the armor to protect the plane and pilot from countless frangible bullet strikes.

So, what could go wrong? Well — things did go wrong, many times, as flying a plane into a hail of bullets was not what many pilots would want to attempt! But they did find the pilots to fill these aircraft and in the next issue, I will continue this story and tell a few tales about those pilots and a bit more about the technology that made these missions one of the most bizarre, little-known stories of World War II.

Until next time, Happy New Year and Bob out …