For most of his childhood growing up in Sun Village, Calif., Ray Wilson thought his father’s service in World War II had only been in the mess hall.

“He was making us dinner one day, and we kids asked him if he learned to cook in the Army,” Wilson said.

“We did everything in the Army,” was his father’s reply.

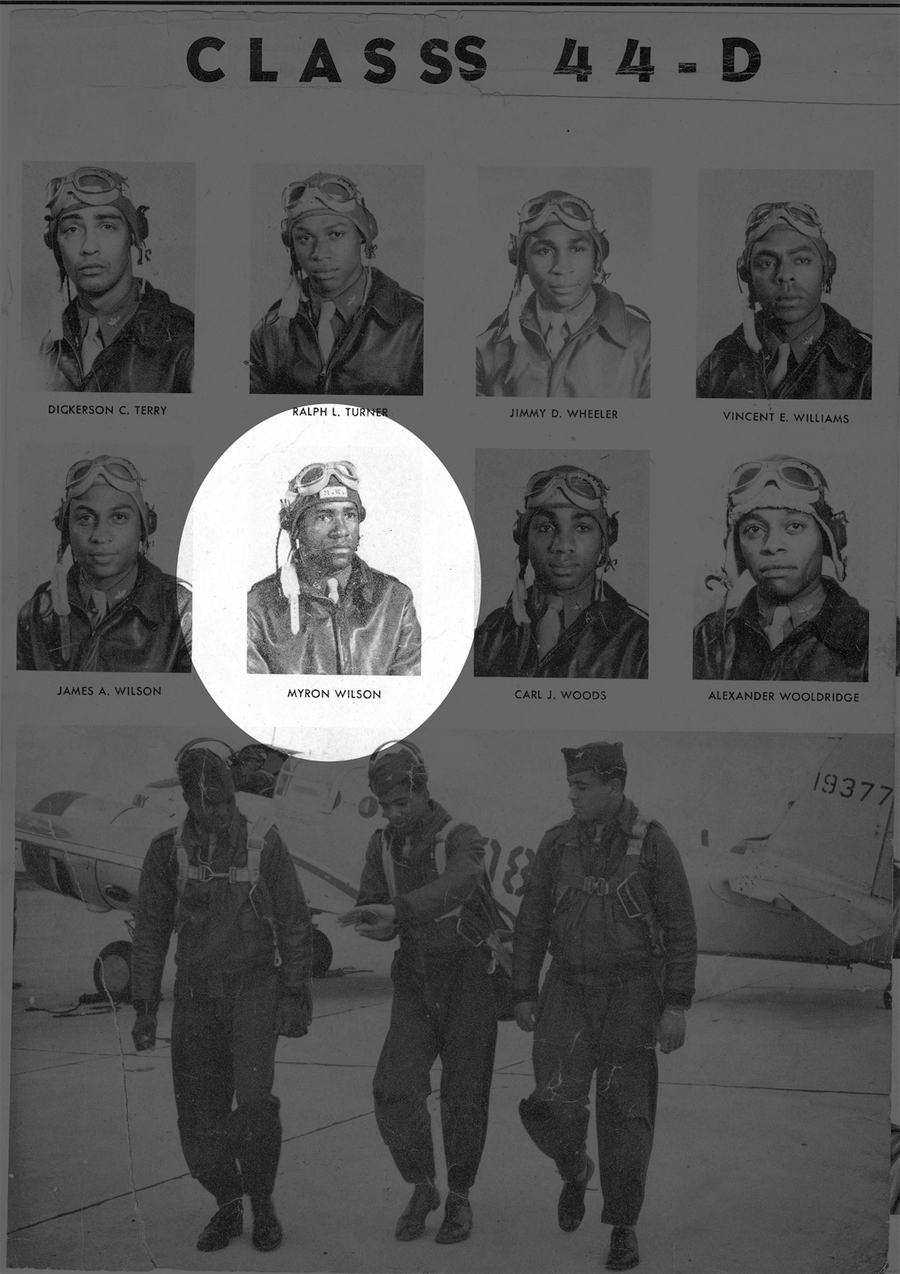

Then, at age 11 or 12, Wilson found out from an older brother that Myron “Mike” Wilson was not a cook in the Army Air Corps, but a combat pilot.

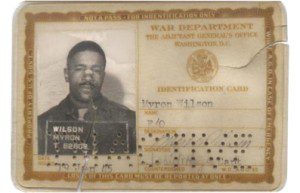

And not just any pilot, but a member of the esteemed Tuskegee Airmen, and who was awarded a Certificate of Valor for flying 47 missions in the European Theater of Operations.

Wilson said his father was very private and unassuming, and his family had to pry information out of him regarding his role in the outfit of 992 African Americans.

Because of Jim Crow laws, segregation and bigotry in the United States, the flying units had all-Black support services: “pilots, co-pilots, bombardiers, navigators, engineers, meteorologists, intelligence officers, instructors, medics, aircraft and engine mechanics, control tower operators, and other maintenance and support staff,” according to government sources.

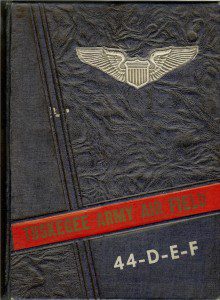

Deputy Wilson made a video about Mike Wilson, using his flight logbook, as well as war footage and still photos in the public domain to show his father’s service and the Tuskegee Airmen’s exploits against the background of World War II. There is a seven-minute version, and one a little more than 20 minutes in length, that puts the war itself in the context of world history. The 20-minute film features footage of Mike Wilson in 1990 talking about his war experience.

“It’s a timeline, inside of a timeline, inside of a timeline,” said Wilson.

The film mentions the planes the 332nd Fighter Group used to escort the Army Air Corp bombers: P-39 Airacobra, P-40 Warhawk, P-47 Thunder, and Mike Wilson’s favorite, the P-51 Mustang.

It took Wilson nearly three years to finish the video, learning the Final Cut Pro editing program as he went.

Wilson made the film because he and others didn’t see his father as a hero, he said. “He was just my dad, he was just the guy who fixes stuff.”

That’s why the film has an “Everyone has a story” tagline.

Like many of the Greatest Generation, Mike Wilson didn’t talk about his service. He did what he needed to do, then went back to civilian life.

“He’s not the only person who is reticent like that, but if we stop and talk to people, we can find out they have some interesting stories, and some of them are pillars of history,” said Wilson.

“You can’t look at everybody as if they are the same.”

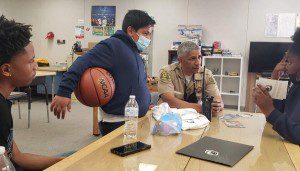

Wilson, a Los Angeles County Sheriff’s deputy for more than 20 years, has shown his film on school visits in the Antelope Valley and to young people in the Sheriff’s Youth Activity League, an afterschool program. The YAL has been around for 20 years, formerly at Jackie Robinson Park, but Wilson took it over in Palmdale, December 2020.

Members of the YAL were “pretty locked into the film,” said Wilson. “I doubted that they were going to pay attention to it, but kids here knew it was my dad, and they can relate to that.”

One of the YAL activities is to make scale models of aircraft of World War II and Korea-era planes.

Mike Wilson, of Shawnee Town, Ill., went to the University of Illinois for a two-year degree, which according to his son, “made him eligible to test for the pilot program.”

“He was accepted to MIT, but they didn’t have scholarships for African Americans,” Wilson said.

So, Mike Wilson was sworn into the Army Air Corp at Moton Airfield in Tuskegee, Ala., on April 4, 1941, eight months before Pearl Harbor, and soloed on Dec. 17, 1943, according to his logbook.

The pilot became a first lieutenant and flew until the program’s end. He was discharged on a compassionate leave but returned to service during the Korean War. Once again, he flew, but only as a sergeant. The newly formed U.S. Air Force refused to reinstate his previous rank.

Wilson said that his father “alluded that it was because of his race,” but didn’t seem too bitter. “He just said, ‘I didn’t get a good deal.’”

The story of the groundbreaking African Americans has fostered many books, documentaries, and feature films. Wilson recalls watching the 1995 film The Tuskegee Airmen starring Laurence Fishburne. The older man said, “It was pretty right on the money,” according to his son.

As the film laid out individual stories, Mike Wilson recognized his fellow fliers. “He’d say, ‘Oh, that’s (John H.) Chavis, that’s (Henry R.) Peoples, that’s (Robert W.) Deiz,’” Wilson said.

One character who elicited the most comments from the old pilot was Commander Col. Noel F. Parrish. “This guy was tough as nails; he was a son of a gun,” Wilson remembers his dad saying. “He was a good man.”

“I knew that meant a lot. My dad didn’t talk much; he wouldn’t say that unless there was some serious context.”

In 2001, the Tuskegee Airmen pilot Myron “Mike” Wilson died of natural causes at age 85. Deputy Wilson says he can still see his father’s handiwork in many Littlerock, Calif., houses he remodeled and home additions he built as a contractor.

But now, those are not the only reminders he has of his dad. “As time goes on, I realize what a treasure that logbook is,” Wilson said.