At any time, there are a couple million paratrooper veterans. But I only know of two who could remember all the words to “Blood On The Risers,” the morbid drinking anthem of any in the U.S. military who aspired to jump from perfectly good airplanes.

“Blood On The Risers,” composed during World War II, is sung to the theme of “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” and the chorus is, “Gory, Gory, what a helluva way to die and he ain’t gonna jump no more!” Most paratroopers can only remember the chorus about the rookie jumper who fell to his death.

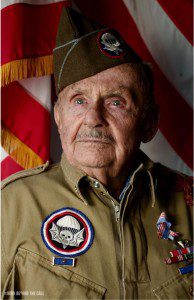

Two World War II paratroopers I know of could sing all the words all the way into their 90s.

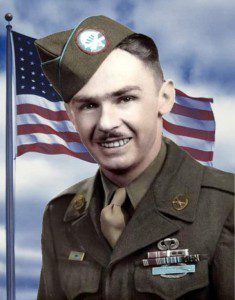

The one I knew personally died Feb. 16, 2022, at age 97. Daniel McBride, a leathery native of the Buckeye State, was a veteran of jumps on D-Day, Operation Market Garden in Holland, and the defense of Bastogne, all recounted wonderfully in the epic miniseries “Band of Brothers.” Dan, a super ambassador of the “Greatest Generation” veteran, was decorated with three awards of the Purple Heart, and a Bronze Star. He ended the war to end the Third Reich at Hitler’s redoubt in Berchtesgaden.

Many in the paratrooper fraternity who got to meet him are aching at the loss of Dan, a sergeant with Fox Co., 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. We ache even though he lived until 97 and was sharing the enjoyment of life with friends and family until the end.

Of the paratrooper anthem, he said, “That song wasn’t meant to inspire us.” Remembering his jump school days in 1943, he said, “The words in the song was a sort of psychological warfare, meant to scare us and make us quit Ö But I wasn’t going to quit.”

Dan and his 101st Airborne buddy, Vincent Speranza, could sing all the words, whether at reunions or joined with fellow paratroopers celebrating in Normandy commemorations of recent years. Recently, at Dan’s memorial celebration in Silver City, N.M., his buddy, “Vinnie,” sang a different song, a clear-throated rendition of “Danny Boy” that would make the Irish weep.

“Oh, Danny boy, the pipes are calling, oh Danny, how I love you so.” Leaning on his cane, the old Screaming Eagle vet stepped down from the pulpit. And we all wept with grief and joy, at the chapel or livestreaming the service on video.

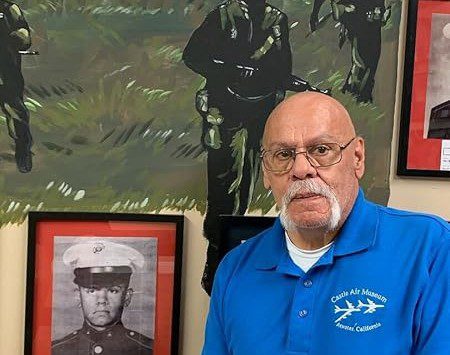

All the way into 2022, Dan McBride was accompanied by his friends and escorts, Tracie Hunter and Dale “Friday” Lindley. Young enough to be his grandkids, Hunter and Lindley were often by his side at events. Hunter, an Emmy-winning filmmaker recently completed a documentary that featured McBride titled “Rendezvous With Destiny,” about the World War II exploits of three 101st Airborne veterans.

At the memorial, Speranza explained to the uninitiated that the term “buddy,” has a spiritual meaning. A buddy is someone you shared combat with, and it is a bond that cannot be experienced by others outside the bonds forged in war.

A few years ago, an Antelope Valley veteran buddy, Mike Bertell, who heads up the AV Vietnam Memorial Wall Committee, told me about Speranza. He had met Vinnie at a 101st reunion.

Vinnie and Mike were 101st Airborne Division “Screaming Eagles” veterans from different wars, World War II and Vietnam. But both knew a place called Bastogne. Bastogne, Belgium, is visited every year by thousands interested in one of the most climactic battles of World War II, the “Battle of the Bulge.”

For Vinnie and Dan, Bastogne was that Belgian crossroads city where the Nazis could not overwhelm the 101st Airborne in the snows of the coldest winter in Europe in 50 years. Surrounded by crack Nazi panzer divisions, outnumbered, and outgunned, the Germans under a white flag of truce offered the Americans surrender terms. The answer from Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe was one word: “Nuts.”

Vincent Speranza wrote his own book about his time in the fight at Bastogne titled, appropriately, “Nuts!”

“Nuts,” was a confusing word to the Germans, but it meant “No surrender.” Vinnie is nearly 100 now, and his 101st buddy Mike is a young 75.

Mike’s version of Bastogne was a fire base in Vietnam carved out of jungle that was named for the 101st Airborne Division’s famous World War II stand. Mike got to hang out with Vinnie a few years ago at the home base of the 101st Airborne, Fort Campbell, Ky. There, they sang “Blood On The Risers.”

Mike was on his own journey of healing from his long-ago war, and Vinnie had a hand in the therapy, with whiskey, a cigar, and a rousing chorus of the paratrooper hymn about the luckless trooper who got tangled in his parachute harness straps called “risers.”

“Glory, Glory what a helluva way to die! And he ain’t gonna jump no more!”

Mike knew Vinnie as a buddy. I knew Dan, as a hero. How did we all come to know each other? In a word, Normandy. Normandy, the rendezvous with destiny on D-Day in 1944. And Normandy now.

Normandy is that large province of France that fronts the Atlantic Ocean, and that reaches north nearly to Paris. It is a beautiful region, known for orchards, potent ciders, dairy and cheese, and thick rows of hedges, hedgerows to aid farmers in protecting their crops. In 1944, Normandy was firmly under the heel of the Nazi boot as Hitler and his legions waited behind their “Atlantic Wall,” in anticipation of the Allies massive effort to liberate Europe from a new Dark Age on D-Day, the “Day of Days.”

Vincent and Dan arrived in Normandy falling from the night sky, shooting. Barely out of their teens, they were with the 13,000 American paratroopers joined by thousands more British airborne troops who were the first to land and fight on D-Day, June 6, 1944. The seaborne divisions would be landing at Omaha, Utah, Juno, Gold and Sword beaches soon after sunrise.

Dan McBride, aboard a C-47 Skytrain with his 101st Airborne brothers, was third in the jump order, and was able to get a peek out the open aircraft door at the English Channel below. The C-47 was a variant of the Douglas DC-3. Unarmed, Gen. Dwight Eisenhower considered the plane essential to winning the war. For Dan, it was the open door in the racketing plane with the wind blowing in. He cranes his neck.

“That was the most magnificent thing I ever saw,” Dan said at a veterans’ talk last year. “It looked like the whole Channel was moving. I didn’t think there were that many ships in the world.”

Then came the fog that broke up the formation of hundreds of transport aircraft. Next, anti-aircraft fire, deadly flak that was tearing into and blowing up some of the planes, while most got through. Jump altitude was 500 feet, and air speed calculated to give the paratroopers as safe an exit as possible.

“Our guy didn’t slow down, he sped up,” McBride recalled. The green light went on, and he followed the first two out the jump door, hitting his boot as the plane banked sharply, “And I somersaulted.”

“I looked down, and I saw the canopy,” he said. “I looked up and I saw France coming at me.”

Upside down, his leg tangled in his riser, he landed in Normandy head-first and was knocked out.

“I didn’t know if it was 10 seconds, or 10 minutes.”

In the pre-dawn darkness, moving behind the hedgerows the first enemy troops Dan feared closing in on him turned out to be cattle. “They said, ‘Mooooo!’” he quipped.

His next encounter was with a real German, with helmet, and machine-pistol.

“I traded a grenade for an MP-44,” McBride recalled, preferring the machine gun to his M-1 carbine.

“I never felt so alone in my life,” he said. With another rustle in the undergrowth, he heard the password challenge, “Flash!” to be responded to with the countersign, “Thunder!” It was a buddy and Dan said, “I could have kissed him.” Soon after, the 101st paratroopers hooked up with a lieutenant from the 82nd Airborne. Soldiers from the two jump division were scattered for miles across Normandy far from their designated Drop Zones.

“Where are we, sir?” Dan asked the lieutenant. The lieutenant’s answer was, “I have checked the map, and as far as I can tell I am positively sure that we are somewhere in Europe!”

With sunrise, the trio spotted a car approaching “that we thought might be this French Resistance we heard so much about,” Dan recalled. But the car was carrying Nazi troops.

Killing the Germans, the three paratroopers commandeered the car and found their way to Saint Mere Eglise, the first town liberated by Americans in France.

“And that’s all we did on D-Day,” Dan said.

Dan gave his dinner talk one year ago to the parachutists, mostly veterans, of the Liberty Jump Team at their new headquarters in Corsicana, Texas. Some of me and my paratrooper brothers and sisters joined Liberty Jump Team, a non-profit, so we can go to Normandy to make a World War II-style commemorative jump on D-Day.

The officer I served with nearly 50 years ago in Cold War Europe, retired Col. Stuart Watkins, is the 82nd Airborne and 8th Infantry paratrooper veteran who recruited me to renew my military parachutist credentials.

“We jumped at Normandy for the 75th anniversary of D-Day,” he told me. “If you want to, you can come and jump.”

At our training Drop Zone in Texas, a bunch of us prepared to honor our World War II legacy veterans with five training jumps, two of them from the same model and vintage C-47 that carried the Airborne armada to Normandy. It put chills down my spine to have my updated jump wings awarded at the Drop Zone by Dan McBride, who also pinned Tracie Hunter and Dale “Friday” Lindley and 20 more military parachutists who exited a perfectly good airplane in flight.

With the pandemic apparently receding, and with hopes that World War II does not give way to World War III over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, we plan to fly to Normandy and fill the skies with descending parachutes for D-Day Obervances, 2022.

Like his thousands of buddies, living and dead, Dan lived the experience of “A Rendezvous With Destiny.” As in previous D-Day liberation ceremonies attended by Dan McBride, Vince Speranza and their brothers from the 82nd and 101st Airborne divisions, the streets and fields will be filled with thousands celebrating the Liberation of France from Nazi Occupation, and liberation from tyranny.

Au Revoir, Dan. “Currahee!” that war cry of the 101st Airborne, and as the 82nd Airborne troopers say, you are clear to jump to heaven. You are Airborne, “All The Way.”