If you search online for “Army Staff Sgt. Wayne C. Abernathy,” you’ll find only one source that can give you extensive details of his time in service — that he lied about his age to register for the World War II draft; that, after a Korean War plane crash, he woke up in the hospital to famed Army Gen. Douglas MacArthur asking if he was OK; or that he and some Army buddies nearly lost a truck to a shark in the Marshall Islands.

The source that made those details discoverable is the Library of Congress. Thanks to its Veterans History Project, you can hear all about the wartime experiences of thousands of service members like Abernathy and how those events shaped their lives. For more than two decades, the Veterans History Project has been working to catalogue the stories of our veterans to make sure their experiences aren’t forgotten. That knowledge is important for the preservation of history and for future generations to learn.

Now, project creators are looking to add the accounts of medical and emergency professionals to its collections.

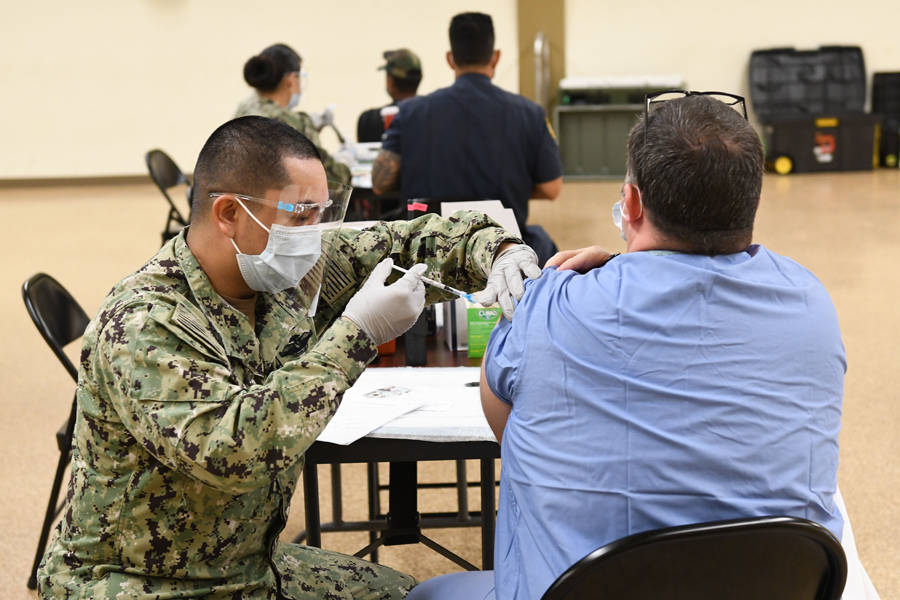

The Veterans History Project currently includes more than 113,000 collections comprised of oral history interviews, photos, letters and diaries. It has often focused on the experiences of veterans in war, including Medal of Honor recipients and many who made the ultimate sacrifice. But in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s now looking to highlight stories from the Commissioned Corps of the U.S. Public Health Service — officers defined as veterans when they’ve completed their service — as well as Armed Forces service members who were deployed to natural disasters, national emergencies and public health crises.

“They don’t have to be medics,” said Monica Mohindra, the director of the Veterans History Project. “It’s not just the people who are in the midst of combat. The whole story of U.S. service is all the different ways that our service members contribute to that larger story. So, if somebody served on the USNS Comfort at that time and they weren’t a medic, but they were serving in support of that crisis, we want their story, too.”

Examples of crises from which they’re looking for first-person narratives include hurricanes Katrina and Sandy, the 1989 Lomo Prieta earthquake, Operation Tomodachi in Japan, the 2010 Haiti earthquake, as well as COVID-19 pandemic response and first-responders from Sept. 11, 2001.

“It is time to increase our collective awareness of these valiant members of our society and to not only give them the overdue thanks they deserve, but ensure their voices are not lost to history,” explained Mohindra.

Quite often, veterans aren’t always chomping at the bit to tell their stories. The Veterans History Project is a grassroots effort that relies on volunteers who are willing to interview and collect information from the veterans in their lives and communities. These accounts bring history alive in a way that helps current and future generations better understand the realities of conflict and crises, as well as the personal effects of service.

“These individual voices take us back,” Mohindra said. “This is the first-person — what it meant to be in conflict or a peacekeeping mission from the personal scale; what that impact was on your home life and what that impact will be like for your community going forward.”

Those who begin a collection are often not the veterans themselves but family or community members in their lives. If you want to help tell the story of a veteran you care about, here’s how.

How to take part

To participate in the volunteer-based archive, go to loc.gov/vets, download the field kit and fill out the required forms to make sure your interview gets accepted and is a useful primary resource for researchers. While the number of forms might seem intimidating, it’s not a difficult process — Mohindra said the forms make the collection as rich and accessible as possible, as well as protect the veterans’ rights.

“The Library of Congress is the home of copyright, and that’s really important to us,” she said. “Veterans who share their stories with us do retain their copyright. They get to decide what happens to their story.”

On the top right of the “How to Participate” page, there’s an eight-minute video that explains the application process. It offers tips on how to prepare for and conduct the interview and describes how to make sure it gets shipped to the Library of Congress without being damaged.

Mohindra also said that new collections don’t have to be about living recipients. She said during the pandemic, there was an uptick in people sending in documents to archive details about deceased family members from World War I and World War II.

How to access the collection

Not only are the accounts of veterans being sought by the project, they’re also accessible to anyone who wants to learn about them, including researchers, students, podcasters, documentarians — even choreographers, Mohindra said.

The Veterans History Project includes digitized collections of audio and video interviews as well as physical transcripts, photos, manuscripts and diaries from service members dating back to World War I. To search the extensive digital collection, visit memory.loc.gov. Items that aren’t digitized can be viewed at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., by making an appointment with a reference specialist.