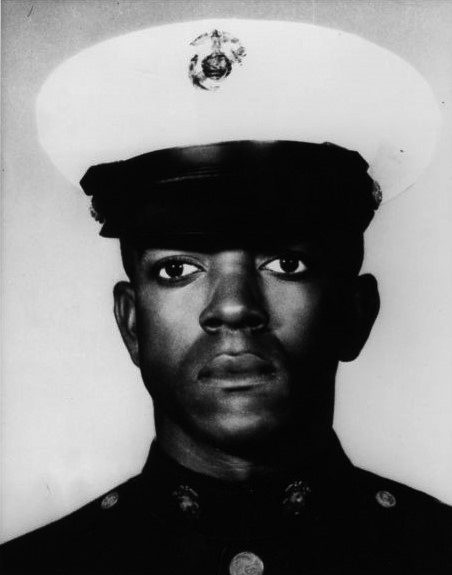

Marine Corps Pfc. James Anderson Jr. had a plan for his future, but when the Vietnam War began, he felt compelled to serve.

The 20-year-old never returned home to fulfill the plans he had for himself, but the valor he showed during his short time in service earned him the Medal of Honor.

Anderson was born in Compton, Calif., on Jan. 2, 1947, to Aggiethine and James Anderson Sr. He was the first boy born to the couple, who already had five daughters. He also had a younger brother, Jack.

Growing up, Anderson liked to sing in the choir; he was also a fabulous dancer and took part in service organizations, such as the Boys and Girls Clubs of America, according to his niece, Denise Johnson-Cross. Anderson played clarinet in the band at Centennial High School and graduated 10th in his class in 1964. Johnson-Cross said her uncle, who was 14 when she was born, wanted to be minister.

After high school, Anderson went to L.A. Harbor College to study pre-law for a year and a half. When the Vietnam War started, he didn’t want to be drafted into the Army, so he enlisted in the Marine Corps in February 1966 and was sent to Vietnam in December. Anderson was trained as a rifleman – even though his sister, Mary, told the Los Angeles Times in 1984 that he said he couldn’t kill anyone.

On Feb. 28, 1967, Anderson had just celebrated his 20th birthday and his one-year anniversary in the Marines when he was put to the ultimate test.

Anderson was serving as a rifleman in Company F, 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marine Regiment, 3rd Marine Division, in the Quang Tri province on Vietnam’s central coast. He and his platoon were on a mission to rescue a heavily besieged reconnaissance patrol when they came upon heavy enemy fire in dense jungle northwest of Cam Lo.

The platoon reacted quickly and began firing back. Anderson found himself on the ground in a tightly packed group of Marines within about 20 meters of the enemy and began firing back at them.

All of a sudden, a grenade landed within feet of Anderson’s head. Without hesitation, Anderson selflessly grabbed the grenade, pulled it into his chest and wrapped himself around it before it detonated.

Anderson’s body absorbed the blast. He was immediately killed. Thanks to his actions, though, the Marines around him survived with just minor injuries.

Anderson’s extraordinary valor and self-sacrifice were a testament to his courage, and that’s why he received the Medal of Honor posthumously on Aug. 21, 1968. His parents accepted it on his behalf from Navy Secretary Paul R. Ignatius during a ceremony at Marine Barracks Washington.

The honor made Anderson the first Black Marine to receive the nation’s highest award for valor.

Anderson’s sister, Mary, told the Los Angeles Times that he did what he did in Vietnam “because of his faith and his belief in mankind. He always cared about other people.”

The USNS Pfc. James Anderson Jr., named for the Medal of Honor recipient, sails during the late 1980s or the 1990s.

Anderson’s sacrifice has not been forgotten. In 1983, the U.S. Navy showed its appreciation for his gallantry by renaming a maritime prepositioning ship after him. The USNS Pfc. James Anderson Jr. was based in the Indian Ocean and carried equipment to support a Marine expeditionary brigade until 2009. His name also adorns Anderson Hall at Marine Corps Base Hawaii.

More recently, a bill passed by Congress in December 2022 will rename a post office in Anderson’s hometown for the distinguished Marine. The bill was introduced in 2020 by U.S. Rep. Nanette Barragan of California, who first heard about Anderson from Compton Mayor Emma Sharif. Johnson-Cross said that Sharif was visiting Anderson’s burial site at Lincoln Memorial Park when she noticed he didn’t have the appropriate headstone for a Medal of Honor recipient. Sharif brought it to Barragan’s attention, who got the ball rolling on the post office legislation.

A park in Carson, Calif., near Anderson’s home, was also named in his honor.

Editor’s note: Medal of Honor Monday highlights Medal of Honor recipients who have earned the U.S. military’s highest medal for valor.