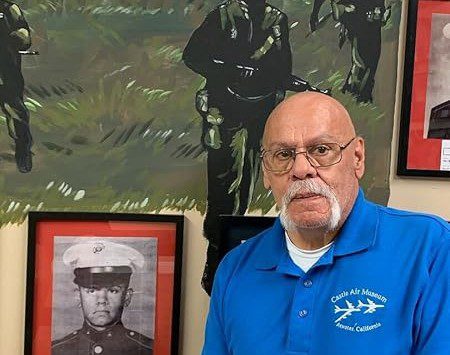

World War II veteran Harold Williams, a retired U.S. Army technical sergeant turned 100 years old in January 2023. Williams served in seven campaigns during World War II.

During one trek toward the end of World War II, Harold Williams and members of the 1st Infantry Division encroached upon a small village near the French-Belgian border.

There, he said, a boy led Williams and his fellow Soldiers to his family’s cottage. The boy’s parents asked Williams’ commander if they intended to stay and if they could safely come out. After Williams’ commander nodded yes, the child’s relatives revealed that for two years they had sheltered a Jewish family from the war.

Williams could see two young faces peering behind a curtain in one of the windows.

Now that the Americans had liberated the village, Williams and his unit then watched the Jewish family’s young daughter, who looked about two years old, walk into the daylight for the first time, he said.

“I saw, with my own eyes grown men crying,” said Williams, who turned 100 on Jan. 23, 2023.

Williams said the memories of war remain with him from the hopeful to the gruesome.

He lives his days quietly now in the shelter of St. Peter’s Nursing and Rehabilitation Center in Albany, N.Y. He has four children, seven grand-children and nine great-grandchildren.

Williams left Europe mostly unscathed, with only a broken finger, he told his family. And he said he carries the burden of knowing he survived while so many U.S. troops did not return. Today, fewer than 389,000 of the 16 million Americans who fought during World War II remain.

“You lay your head on the pillow at night and you think ‘wow I got to come home,’” he said. “A lot of them never had a homecoming.”

And even from his room in St. Peter’s, decades removed from the war, the guilt haunts him. As does the ruins of cities torn apart by war and the dead from both sides lying in the aftermath.

“He remembers everything,” his granddaughter, Julie Preder said.

Preder, as a former suicide prevention manager for the New York National Guard, saw many of the same symptoms in veterans diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. Williams kept the atrocities he witnessed hidden for most of his life. But, later, during interviews, he revealed some of his secrets.

The New York native can still recall the day that he and his fellow Soldiers stormed the shores of Normandy to a waiting German Army.

Many Soldiers in Williams’ unit did not survive; the Germans cut down 44 men instantly. German Soldiers waited from the vantage point of a tower where they fired upon vulnerable American Soldiers at Omaha Beach. Dead troops already lined the shoreline as Williams and his fellow Soldiers approached.

During the Battle of the Bulge alone, enemy forces wounded more than 47,500 American Soldiers and more than 19,000 lost their lives. German forces took 23,000 U.S. troops prisoner. To date 291,557 Americans died during the war according to the Department of Veteran’s Affairs.

“I guess most of us just wanted to forget it all,” he said. “You don’t ever really forget it; life has to go on.”

His unit also faced the Battle of the Bulge, where Hitler attempted to divide the Allied forces during a secret night operation at Ardennes. Enemy forces took more than 23,000 American Soldiers prisoner and over 19,000 lost their lives. Williams participated in the American counterattack.

“It was a nightmare,” he said. “We couldn’t believe what was happening.”

Williams also engaged in the battles of Huertgen Forest, Elsenborn Ridge and Leipzig, before deploying to Czechoslovakia. In all, Williams returned to New York after taking part in four major campaigns and 424 total days of combat.

“My grandfather will be the first to say, he definitely has survivor’s guilt,” Preder said.

“The one thing that he has said over and over throughout my life has been he walked out of that war with a broken finger. And [his] friends didn’t.”

During the D-Day invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, then-Lt. Col. Bennett led the second wave of U.S. troops against heavy machine gun fire. Bennett’s troops suffered 50 percent casualties. After reaching the safety of a nearby ridge, Bennett saw enemy forces had trapped Allied forces.

Bennett then reorganized the remaining Soldiers in his infantry, four tanks and anti-aircraft unit, he led a successful counterattack. Williams recalled that during the battle with Allied Soldiers falling around Bennett, the officer continued to fight even after suffering two wounds.

He has campaigned for Bennett to receive the Medal of Honor for his actions. “He should have received the Medal,” Williams said.

Although the trauma plagued him through the years, an unshakeable bond formed during the war carried him through the difficult times.

“The comradeship [I] had … I wouldn’t take anything before it,” he said during a 2007 interview for the Library of Congress. “Money can’t buy it.”

Williams continued to keep in touch with fellow veterans in the decades after he left active duty in 1945, including his commander, retired Gen. Donald Bennett and a Soldier from Missouri named Russell McGee who served as Williams’ driver.

Decades after the war Bennett, who later reached the rank of general, took Williams and his son, David, on a tour of the West Point campus. David later enlisted in the Army.

Celebrating a lifetime

In January Williams received dozens of birthday cards from relatives, friends and veterans honoring him for his time on the front lines. About 60 nearby residents including, veterans, attended his birthday celebration outside of St. Peter’s. Because of physical limitations, Williams, could not physically be at the celebration but instead waved from the window of the nursing home.

Williams grew up in the small upstate New York town of Valatie, about 20 miles south of Albany. As a teenager, Williams dropped out of high school to help earn additional income for his family. Williams attended basic training at Fort Dix, N.J., in June 1942 before going to Fort Knox, Ky., for additional training.

He enlisted in the Army in 1941 and went on to participate in seven campaigns in Europe and Africa, Williams served as a radio operator that travelled with the infantry.

In July 2022, the New York State Senate inducted Williams into its Veterans Hall of Fame for his meritorious military and civilian service Williams became a postal worker after leaving the Army.

“I was deeply honored,” said Williams who has also took part in American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars organizations.

Ichabod Crane Central School presented Williams with his high school diploma, more than eight decades after he dropped out of school.