LANCASTER, Calif. — First, the boa constrictors came. Then, the Japanese.

Fred Emmerich, 95 years old, energetic and with a twinkle in his eye, grins and says, “My story is very amazing.”

Emmerich, a resident at the William J. “Pete” Knight Veterans Home in Lancaster, has a story to tell that is so compelling books have been written about it.

His residence at the veteran’s home is decorated with art and photos meaningful to his amazing life. The walls room of his are covered with photographs of wild animals, of Hitler and Mussolini, of a Japanese Mitsubishi Zero fighter plane, arranged alongside paintings of jungle huts and outriggers. And photos of snakes. Really big snakes.

What sounds like the opening acts of an Indiana Jones movie unfolded as chapters in one family’s odyssey to escape the Holocaust that consumed six million Jews in Europe. Fred’s family, and Fred himself, navigated some of the worst perils of the 20th century.

Born into middle class comfort, all that changed with the rise of Adolf Hitler. The Nazi threat descended, with the Gestapo checking his family’s papers as they fled from Germany just ahead of the outbreak of World War II and the threat of the looming Holocaust.

With savings carefully amassed, Emmerich’s mother and stepfather bribed and bought passage to enable the family to escape the Third Reich, first by rail to fascist Italy, then on a steamer bound for the Pacific. The family got as far as Manila, capital of the Philippines. Next, they migrated further out to the second largest island, Mindanao. Even there, they were not safe.

The human peril shifted to the dangers of island survival. After a hurricane in the Philippines wiped out a family homestead, a tide of boa constrictors slithered out of the jungle in the flooding.

Soon after the Emmerich family farm was swallowed by the hurricane, the Japanese swept in and began bombing their island refuge right after the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor. Of all the German Jewish citizens who fled the Third Reich, Emmerich is probably the only one who was wounded by a Japanese bomb shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The Philippines Constabulary ordered evacuation of the city of Davao after Japanese bombing commenced a day after Pearl Harbor. Fourteen-year-old Fred Emmerich’s wound was bloody, and infection could be lethal. Liesel, his mother, yes, she also was “very amazing,” and had military medical training.

“My mother was a nurse on the front line with the German army in World War I,” he said. “She knew how to do things.”

With his wound dressed by her skirt hem, and the aid of a wheelbarrow retrieved by his older brother Ernest, mother and brother muscled young Fred back to a hospital in Davao city that had escaped the bombing.

Hazards of the battles between Japan and the United States would compel the family to flee again, to sail about 20 miles in an open boat to a remote island populated only by Moro indigenous tribes.

“The way we got the boat, a Japanese lifeboat, is we moved it a little bit at a time along the beach, so they did not notice,” Emmerich said. “Those guards were not so smart.”

By the dark of night, the family piled a few belongings into the boat, rigged a sail made with a sheet, and took to sea. The tiny island of Samal became the hiding place where the family Emmerich would survive off the land and bounty from the sea until the end of World War II.

The Emmerich men adopted local native loincloth attire and became as sun browned as the locals.

“I am a survivor,” Emmerich says. “Do you know what that means?”

Survivor can mean many things, a survivor from a storm, or fire, or a survivor of the Holocaust. That, Emmerich is, most of all.

Emmerich lives at the California Department of Veterans home, surrounded by family photos, paintings and flags of countries visited, and countries escaped from.

“He is so cheerful,” said Elvie Ancheta, administrator of the Lancaster veterans’ home. “He is always smiling and willing to talk.”

Born in 1928 to Julius and Liesel Konigsberger, with the birth name Alfred, Emmerich was too young to grasp the calamity that would fall to Jewish people as the Third Reich rampaged and murdered its way across Europe.

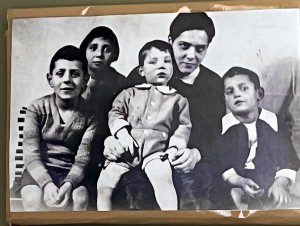

After bearing four children with the husband who was affluent but 20 years her senior, Fred’s ruggedly independent mother Liesel divorced Julius. Later, she married Henry Emmerich, an adventurous entrepreneur who was trying desperately to find a safe haven for his new family. As an “Aryan” married to a Jewish woman, they were all in danger. In the early 1930s, the new couple placed the children they shared into orphanages that would shelter Jewish children before the Nazi grip tightened.

“Can you imagine seeing your mother walking away? And you are left in an orphanage?” When Liesel returned to retrieve her three boys years later, Fred did not recognize her. She had arrived in the nick of time to save their lives. Other family members were killed in the Holocaust.

In 1939, “We were on the last train out, the last ship out,” he said. “Otherwise, we would have been fried.”

As World War II began in Europe, thousands of Jewish refugees had arrived in Manila, capital of the Philippines, at the time a U.S. Trust Territory. Filipino people welcomed the refugees, but the U.S. State Department was indifferent or hostile. For many, Manila was the last stop before Japan attacked, bringing the United States into World War II.

Japan’s attack on the Philippines began within 24 hours of the Dec. 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor attack. When the Japanese bombed in the vicinity of Davao, with 13-year-old Fred wounded, the family needed a new plan as soon as Fred recovered. He still carries the deep scar.

It turned out that his stepfather was a man of mystery who operated a shortwave radio, and aided Filipino guerrillas fighting the Japanese. Fred’s mother Liesel was often away with him.

“He was a spy,” Emmerich said. “He could never be in one place. We lived many years in the jungle in order to escape from the Japanese. But you could go two feet into the jungle, and no one would ever see you.”

With the adults away, curiosity about the Pacific war prompted Fred and one of his brothers to sail out to sea in a native canoe. “We wanted to see some of those battleships! We weren’t out there more than five or ten minutes, and a Japanese patrol boat picked us up.”

They were brought back to Mindanao for questioning.

“I was just a smart kid,” he said, chuckling. “I was fluent in German, and Spanish, and some Filipino. But there are hundreds of dialects, so any educated person would speak Spanish.”

The Japanese military authorities spoke no German, but located a Japanese officer who was a linguist. This worked to the Emmerich boys’ advantage, as Germany was an ally of Japan. His brother kept quiet, and Fred bluffed gamely, never mentioning they were Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany.

“I told them ëThis is where we live! This is our home!’ I gave them a big snow job,” he said. “They could kill us, or they could let us go. They let us go.”

On the island, the family subsisted on local game. At least once, when American warplanes dumped a bomb load into the ocean, the multitude of stunned fish that surfaced became a feast of much needed protein.

“The concussion doesn’t kill the fish,” he said. “We picked up the fish.”

The end of World War II in the Philippines was signaled by the appearance of American warplanes, and the absence of Japanese fighters and bombers.

“At a certain point, there was no bombing,” he said.

The war that began with Japan’s attacks on Pearl Harbor and Manila ended in 1945 with the detonation of two atomic bombs.

Sailing in their outrigger canoe 17-year-old Fred and one of his brothers were spotted by an American P.T. boat speeding along in the strait between Mindanao and Samal. It was one of the small, fast patrol-torpedo boats of the kind skippered by future President John F. Kennedy in the P.T. 109 saga.

American sailors encountered two Caucasians in loin cloths, with wild hair, and native garb, who used sign language instead of English. Soon enough, an American landing craft stopped at the island, and transported the Emmerich family back to the big island of Mindanao.

“At first, they did not know what to make of us, and thinking we were German, they were not very friendly,” Emmerich recalled. “But once they understood who we were, we were welcomed with open arms.”

With sponsorship from an American family who befriended them in Manila, and with help from international Jewish organizations, at long last, they secured passage to the United States. Boarding a World War II Liberty Ship, they disembarked in San Pedro, Calif., in 1948. They resettled in San Francisco.

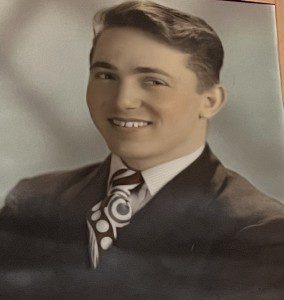

A strapping young man at entry into adulthood, Fred soon found himself drafted into the U.S. Army.

“I was willing to serve my country,” he said. “I had a good time in the Army. I was willing to go to Korea, but the Army told me ëThat’s the last place you’re going. We need you elsewhere.’”

His mechanical aptitude and experience from an apprentice program served him so well that the Army decided they needed him working on base construction projects in a variety of locations including Elmendorf, Alaska.

He was quickly promoted from private to staff sergeant, of which he remains proud to this day. He was told his rise would be rapid if he remained, but he wanted to return to civilian life as a proud veteran and continue his training to be a tool and die maker.

Fred married JoAnn, a girl he met and courted in San Francisco. Together, they raised a family. As hard-working Americans, they worked hard, prospered and traveled, even returning to Frankfurt, Germany, where his odyssey began.

“Timing is everything,” he said. “I have always been lucky.”