PALMDALE – It was a choice many young men of earlier generations needed to make quickly: some form of reform school, jail, or join the military.

For Palmer Andrews, a teenager raised haphazardly in the tough neighborhood of Chavez Ravine long before Dodger Stadium was built, it was a choice he made about a year after the Empire of Japan bombed the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

“I decided my needs might be better met in the military,” Andrews recalled. “I liked the uniform, so I joined the Marines.”

Andrews, 17 at the time, never even got the chance to wear those fancy Marine Corps “dress blues” that set the tone for uniform fashion.

“He never even got a set of dress blues because he was either training or in combat his whole time in the Marine Corps,” his grandson, Allen Quinton recalled.

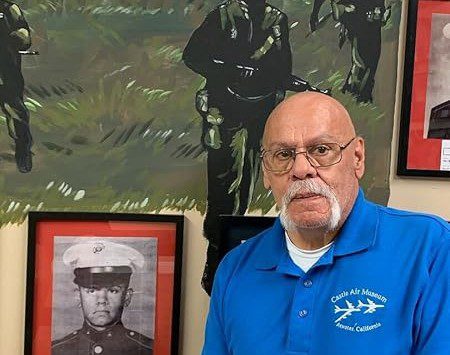

Andrews, who served with the legendary Lewis “Chesty” Puller during World War II in the Pacific, and who gained prominence as the Antelope Valley’s celebrated senior Marine, died Thursday, Jan. 11. He was 98.

Andrews went on to a successful life in insurance sales and was also acknowledged as a lay scholar of the early 20th century author Jack London. The veteran died early Thursday, surrounded by family members and friends. He was with his grandson, Allen, his daughter Jeannie Quinton, and caregivers Dee Black and Tony Tortolano.

Andrews served as a Private 1st Class with the 1st Marine Division and served in the storied Marine unit India Co., 3rd Battalion, 5th Regiment. These are significant because they indicate who Andrews served and fought with.

“I was not a hero,” he was known to say. “But I served with heroes.” He added, “I got to come home because of the ones who could not come home.”

The retired executive had lived with his grandson, Allen Quinton, in Palmdale, for the last 10 years.

“He was my best friend,” Quinton said. “Since I was 9 years-old, we were just that way. At my wedding, he was the one who tied my tie.”

Once, when Quinton was searching for something in a drawer, he ended up picking up a heavy piece of metal attached to ribbon.

“I asked him, ‘What’s that, grandpa?’ He answered, ‘Oh, that’s a Purple Heart,’” and he said it like, “Oh, those are car keys or something.”

That was characteristic of Andrews’ modesty. He was born Nov. 23, 1925, and grew up in the Chavez Ravine area of Los Angeles, decades before the Dodgers migrated from Brooklyn and razed the neighborhood to erect Dodger Stadium.

By his own account, growing up with a succession of “uncles,” he was offered reform school, or the military. He joined the Marines, with his mother signing papers for him.

“He went to boot camp at the beginning of 1943,” Quinton said. “He was in the Marines from the end of 1942 until 1945.”

During his time with the 1st Marine Division, Andrews fought in campaigns on the islands of New Britain, Peleliu, and Okinawa. Those names are all embroidered “battle streamers” attached to the red and gold Marine Corps flag.

On New Britain, it was “Chesty Puller” who singled him out with more than 100 other Marines to press forward on what became known as “The Gilnet Patrol,” a long-range reconnaissance to clear the island of Japanese. To have served with Puller made Andrews himself a historical footnote, as it was Puller who became the most decorated Marine, still, with five awards of the Navy Cross, the Distinguished Service Cross, and Silver Star.

During the Gilnet mission, the jungle was a more formidable adversary than the Japanese, but the rigors of patrol toughened the Marines for the island fights that lay ahead.

Peleliu was a small coral island with an airfield. An amphibious landing and battle that the division commander estimated would take four days turned into a bloody, drawn out two months, with ferocious Japanese counterattacks that resulted in more than 1,300 Marines killed, and more than 5,200 wounded.

Andrews said the memories were difficult, but he revisited them with his grandson when together they viewed “The Pacific,” an epic HBO miniseries that was a successor companion to “Band of Brothers,” both produced by Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks. The attack on the airfield, depicted in “The Pacific” was a horrific blaze of machine gun and artillery fire cutting down Marines on the run. Temperatures on the coral atoll topped 115 degrees and claimed many Marines as heat casualties, with shortages of drinking water a constant.

“I never realized what my grandfather had been through, but how could I?” Quinton said. “He would just say ‘We did what we had to do.’”

The last campaign of World War II for Andrews was the battle for Okinawa, the final land battle of World War II fought by Marines and the Army before the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki —ending history’s largest conflict.

On Okinawa, during 11 weeks of fierce combat, casualties were worse, with 12,500 Americans killed, and 36,000 wounded or missing. U.S. military records cite nearly 80,000 Japanese troops killed, and thousands of civilians, including those who jumped off cliffs to their death.

At the end, Andrews was among the living, returning home with that Purple Heart for his wound sustained in combat.

Soon after the end of World War II, Andrews joined the newly formed U.S. Air Force, and served stateside as a reservist during the Korean War.

During a successful business career, Andrews became an impassioned lay scholar of the life of author Jack London, author of dozens of novels, but best remembered for “The Call of the Wild,” and “The Sea Wolf,” made into movies several times. His collection, “Jack London in Context,” is housed at Sonoma State University in Northern California where London lived at his imposing residence in “The Valley of the Wolf.” Andrews donated his comprehensive collection of books, letters, and memorabilia in 2014.

The reform school bait kid from Chavez Ravine was impressed that London was self-educated and achieved success and fame.

“I started reading and collecting Jack London over fifty years ago,” Andrews wrote in the introduction notes to his collection at Sonoma State University. “One of the many things that fascinated me was London’s belief that, through books, one could become educated on any subject. I think this is what initially drew me to Jack and made me want to know more about him.”

In recent years, Andrews gained prominence in the Antelope Valley as the senior Marine celebrated on Nov. 10, the Marine Corps Birthday. It has become the biggest annual fete held at Bravery Brewing, a favorite gathering spot of the Antelope Valley’s military community.

Several times, Andrews was introduced by another famous Marine, real life Marine Corps Drill Instructor and actor R. Lee Ermey, the star of “Full Metal Jacket.” Ermey and his partners at Bravery— Bart and Sandra Avery— ensured the Andrews, the WWII veteran received the first slice of the ceremonial Marine Corps birthday cake.

Most recently, in November before Veterans Day, Andrews was an honored guest of the Veterans Military Ball hosted by the Coffee4Vets organization.

“Palmer was an amazing man,” said his friend, Tony Tortolano, another Marine was named Palmdale’s Veteran of the Year. “I will never know a better man. I am just so glad I got to be his friend.”

Andrews is survived by his son, Larry Andrews, and daughters Jeannie Quinton and Christine Johnson. He had nine grandchildren, six great-grandchildren, and nine great-great grandchildren.

Memorial plans were pending. His grandson said a tribute celebration is also being planned.