In 1933, the skies above Rogers Dry Lakebed were quiet except for the ever-present wind.

In September of that year, everything changed.

A small contingent of Army personnel arrived to begin building the first military presence at the installation that would become synonymous with advancements in aeronautics and airspeed.

Lt. Col. Henry “Hap” Arnold, acting as the interim commander of March Army Airfield in Riverside, Calif., needed a location to train his aircrews in bombing and gunnery.

Having heard about the large, flat surface of the dry lake, he figured he had found the ideal location for those efforts and sent a team of five soldiers into the Mojave Desert to lay out a bombing and gunnery range. They set it up in an area on the eastern shore of the dry lakebed.

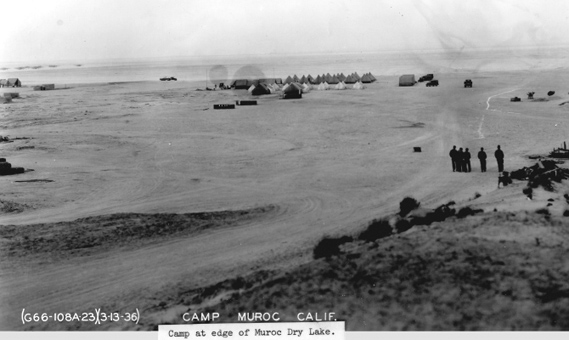

Called “Camp I” in early records, it consisted of tents and circular bombing targets in the desert. Though the aircrews would fly in and out from the lakebed, a small detachment was assigned to the semi-permanent camp on the eastern edge of the lakebed. Originally called “the Muroc Lake site,” the official name of that little station became the Muroc Bombing and Gunnery Range in 1940.

The installation consisted of tents for more than a year. The first building constructed was the combination barracks/mess hall. A permanent headquarters was built by 1936. They also added a water tower for both drinking and firefighting. In 1937, Congress set aside funds for purchasing private lands around the lakebed to allow for bigger Army Air Corps operations at the Muroc site, which became more important as an increasing number of Air Corps units took advantage of the lakebed and training facilities at Muroc.

It took until 1940 for the sales to take effect. Shortly after the outbreak of the Second World War, the Army built a new training base named Muroc Army Airfield (present-day South Base) and the Bombing and Gunnery Range became known as East Camp until it was shut down after the war.

The initial establishment consisted of only a handful of men.

Master Sgt. Harley J. “Fogie” Fogleman commanded the 20 men who built the first structures. The tents they erected relied on coal-fired stoves for heat and an old, frequently out-of-service generator for electricity. Some local residents took to calling the Range “The Foreign Legion of the Air Corps.” In fact, Fogleman noted that they “couldn’t get a commanding officer. Commissioned officers would come up from Los Angeles, take one look at the place, and take off for LA again without even shutting off the motors of their planes.” Fogleman remained the non-commissioned officer in charge of the range until 1942.

Due to its location, all supplies “had to be brought in from March Field.” When Arnold petitioned Congress for funds “to make this site fully effective,” he listed the needs: “Railroad siding, storage facilities for gasoline and oil, quarters for caretaking detachment (including water supply and sewage disposal), improvements to land[ing] field, [and] triangulation stations for the recording of bombs.” Crucially, he requested these items in October of 1935, more than two full years after Fogleman established the site.

That petition to Congress spelled out the costs as follows: land owned by Southern Pacific Railroad and private citizens would add up to roughly $130,000 and the physical improvements would total roughly $50,000. Though Arnold wanted roughly 81,000 acres of land for the installation, the government already owned 38,720 of those acres. He described the land as “desert country, covered with scrub, mesquite, & sage, and totally unfit for cultivation or habitation.” Arnold told Congress each acre would cost about three dollars. When the War Department pursued the purchases in 1940, they brought in surveyors from the Bakersfield area (whom the locals felt undervalued the land) and bought up much of the land through eminent domain.

The most famous event at the gunnery camp occurred in 1937.

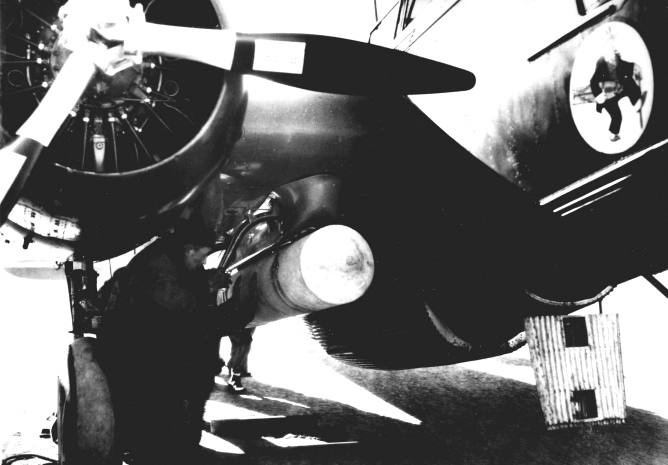

In May of that year, the Muroc Lake site played host to a large-scale war game exercise for a large portion of the Army Air Corps in order to “test the full strength organization of the different type of units” in the Air Corps.

The initial plan called for the participation of more than 2,000 active duty personnel and 13 squadrons of bomber and pursuit aircraft. It also required the 63rd Coast Artillery Anti-Aircraft Division from San Pedro, Calif., to defend the lakebed from the bombers. The Muroc portions of the exercise ended up involving more than 300 aircraft, which was “virtually the entire United States Army Air Corps.”

In addition to its strategic and training value, the exercise caught the attention of the local community.

As early as March 1937, stories ran in the Antelope Valley Ledger-Gazette describing the upcoming event. The exercise began on May 11 after several days of transporting personnel and materiel in preparation. Maj. Gen. Frank M. Andrews, the Chief of the Air Corps, designated May 14 as a day for “the public to visit Muroc Bombing Range. The defending forces there will repel an air attack between the hours of 1 p.m. and 3 p.m. on that date.”

This effort differed from the normal exercise attacks that normally occurred in the early hours of the morning. Though not used in the public display, the simulated attacks included actual drops of tear gas to train both the attacking crews and the defending ground crews in using and responding to the gas. They also tried using smoke screens to interfere with the gunners’ ability to shoot down attacking aircraft. This turned out to be a double-edged sword since it not only proved capable of blocking the defenders’ aim but also kept the attacking bombers from achieving “a high degree of accuracy, stated observers.” May 22 marked the official end of the large-scale exercise when the Anti-Aircraft Division began packing up for its return to San Pedro.