The goal of getting more underrepresented groups interested in STEM is admirable, but not simple.

Some believe you need to catch children’s interest early, especially girls. A 2017 survey of 11,500 European girls, commissioned by Microsoft, puts 15-years old as the age when girls stop being interested in STEM subjects.

“Why Europe’s girls aren’t studying STEM,” points out that female children become interested in math and science around age 11, so there is only a four-year window to spark their curiosity and illustrate how they might fit into an ever-increasing technological work force.

“Across 35 European countries, fewer than one in five computer science graduates are women. Interest in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM subjects) drops off far too early. In fact, the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA)2 reveals that boys are far more likely than girls to imagine themselves as ICT professionals, scientists or engineers. This is a major issue for both the current and future jobs market,” the study said.

One of the most important aspects of inspiring girls is representation, a point brought up repeatedly by female pilots and engineers in a 2023 Aerotech News special edition. “If you can see it, you can be it,” is a familiar refrain.

Here are the stories and advice of those women interviewed who encourage other young girls and women to challenge themselves and find success in STEM-related fields.

Carrie Worth: Who is missing at the table?

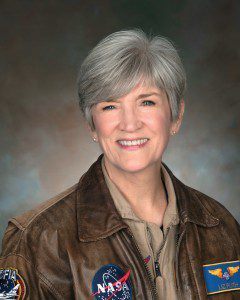

Carrie Worth, research pilot and Gulfstream lead project pilot at NASA Armstrong Flight Research Center at Edwards, Calif., can tell you the exact moment she decided she wanted to fly.

Growing up in Big Bend, Wisc., with relatives in Fond du Lac about an hour away, the Oshkosh EAA Fly-in was a yearly summer outing for her family, “I distinctively remember one year when I was in grade school, and I was starting to get more interested. I knew I liked airplanes. I thought I might wanna fly,” Worth said.

During an aerobatic performance with an EXTRA EA-260 plane, Worth was “watching this pilot do these things that I couldn’t even believe are possible with an airplane.” Naturally shy, the eight- or nine-year-old turned to her father as the plane taxied in and said uncharacteristically, “I wanna meet the pilot; I wanna know how he did that.”

As the young girl watched the glamorous female aerobatic pilot Patty Wagstaff step out of the airplane, Worth turned to her father and said, “Now I can be a pilot.” “I was exposed to aviation at a young age, but it wasn’t until I saw her get out of the airplane that it clicked,” Worth said. “I knew then.”

Now, after a 21-year military career where she logged more than 5,800 hours of flight time, including more than 1,100 combat hours, and working as an instructor pilot, evaluator pilot, and aircraft commander in multiple aircraft, and aircraft commander in multiple aircraft, including the C-21A, M/HC-130P, and CN-235, Worth is the one speaking to and inspiring young girls to become pilots.

Having that personal connection with someone who looks like you and is doing what you yearn to accomplish is so important in getting underrepresented people into aviation, according to Worth.

“There’s a there’s a great organization called Sisters of the Skies. And it’s made up of Black women, who are less than half of one percent of the aviation world. And that’s not even getting into breaking it down into maintenance and air traffic control,” Worth said.

That’s why she and fellow pilot Jennifer Aupke started The Milieux Project, a 501(c)(3) with a mission to connect girls to aviation.

“We like to go out and volunteer to these lower income neighborhoods and elementary schools where the kids maybe don’t have any professional role models in their lives.”

“So, it started as a small group of women saying, ‘We’re just gonna get pictures and videos and information of us out there,’ and now it’s just grown. It’s huge. And they’re making a difference because little girls have someone who looks like them.

Now Worth spends time mentoring with TuskegeeNEXT, PreFlight Aviation Camp, and NASA STEM outreach programs, heeding the words of a male commander who told her, “Carrie, when you have a seat at the table, your job is look around and see who’s missing. Be that advocate. Be that voice.”

‘Patty’ Ortiz: TV show solidified dream of space

As a child, Patricia “Patty” Ortiz thought she wanted to be an astronaut. But when she saw a television episode of Punky Brewster a few weeks after the Challenger disaster, she was positive. The show, with a cameo by astronaut Buzz Aldrin, was meant to reassure kids that they shouldn’t give up on their dreams; that bad things happen, but brave pioneers push on.

And the seven-year-old Ortiz recommitted herself to her dream of space. After many years, she hasn’t left Earth’s atmosphere yet, but her work has.

In Moscow in 2016 Ortiz collaborated with international partners Roscosmos and Krunichev Space Center to assess a contingency freeze scenario for the Russian segment of ISS Functional Cargo Block on the International Space Station where she was the only woman on the engineering team.

Now, as deputy project manager of Orion Heat Shield Spectrometer for Team Artemis — she has a part in putting a woman and the first person of color on the Moon for the first time and establishing a base for Mars exploration.

After the Punky Brewster airing, “I really was very gravitated towards the math and science courses. Growing up, I excelled in those courses, and so I did quite a bit of making sure that I was keeping up with my math and physics courses, but I also tried to stay really well-rounded,” Ortiz said.

She credits her athletic coaches and her single mom for modeling leadership and good work ethics. Ortiz is a first-generation American and first in her family to go to college. Her mother immigrated from El Salvador alone with Ortiz’s three siblings shortly before the civil war broke out. Growing up in South Central Los Angeles with a single mom and without academic guidance inspired Ortiz to join the Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers at the University of California, San Diego.

“The mission of the organization is to change lives, to empower the community through STEM awareness – accessing it, supporting it,” Ortiz said. “I want to get these young kids excited, and to get them motivated. You know, a lot of times kids get scared of the math and physics. And it is almost crippling for them, and I hope that my story inspires young kids and motivates them to continue to study hard and pursue these STEM fields.”

Now Ortiz will oversee Orion Heat Shield Spectrometer on Artemis II through V. Currently, Johnson Space Center is building all of the OHSS box for the four missions.

Ortiz calls it “incredibly exciting” to be a part of the Artemis mission.

“It’s a small footprint into getting boots on the Moon and that’s extremely exciting to be a part of,” she said. “We don’t have anyone that looks like me doing these amazing things. So, for me, it’s extremely exciting to know that now the first woman will be able to land on the Moon. And – beyond, we’re going to continue to explore.

“The sky and beyond is the answer.”

Readers can follow Patricia Ortiz at her inspirational Instagram page “Latinas Need Space

Elizabeth ‘Liz’ Ruth: Inspired by flying pediatrician

As a child living on Naval Weapons Station China Lake in California’s Mojave Desert, Elizabeth “Liz” Ruth received her medical care in an unusual way.

The children on the remote Navy base were visited by a female pediatrician who flew in from Lancaster, Calif., in her own private plane.

“So, at that time, I guess I just really looked up to her and thought well, that would be a great life, you know, be a doctor and have my own airplane.”

“So yes, she was my inspiration,” Ruth said.

“And it never, even though I wanted to fly, never once occurred to me that I could be a professional pilot because I never saw a woman professional pilot. Even airlines, you know, there was just no women pilots for me to see,” Ruth said.

“I could see myself doing that because she was doing it. And for someone who wanted to fly so much, it’s kind of surprising to me now that I didn’t have the imagination to see myself as a professional pilot. But it does go to show that it’s hard to be what you don’t see.”

The plan was to go to college, then medical school to have a job that paid enough so Ruth could afford a plane.

But in 1973, when Ruth was in high school, the U.S. Navy started training aviators for the first time since World War II, and in 1974 the woman graduated who would demonstrate a path to the skies for young Liz Ruth: Rosemary Mariner.

“Rosemary was in the China Lake test squadron and flew airplanes to test missiles for my dad, who was an engineer, and he introduced me to her,” Ruth said.

“Once I saw her, then everything became very clear to me. Oh my gosh, I can skip the whole medical school thing, and I can be a professional pilot.”

After college, Ruth joined the U.S. Air Force, and became an active-duty pilot serving as an instructor pilot, check pilot and aircraft commander for the T-38 and T-43 from 1981 to1989. She left the military with the rank of captain and went to work for United Airlines.

She flew the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), for NASA, a modified Boeing 747SP with the world’s largest airborne astronomical observatory. After SOFIA was retired she learned to fly the RQ-4 Global Hawk surveillance drone that does telemetry for missile launches, and in 2023 she was also flying NASA’s Gulfstream II.