by Cathy Hansen, special to Aerotech News

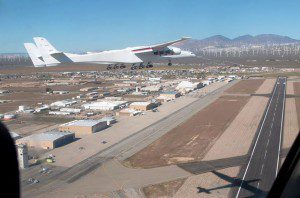

A remarkable and exciting presentation was streamed via Zoom on Aug. 31, 2021, spotlighting the largest flying airplane in the world — the six-engine, composite Stratolaunch carrier aircraft that will launch hypersonic test vehicles.

Detailed information was shared about designing, building and flying this giant machine that has been given the nicknamed of “Roc,” as a tribute to the giant bird of Arabian and Persian mythology.

Dr. Zachary C. Krevor, Stratolaunch LLC chief operating officer, gave opening remarks. He is responsible for overseeing many of the programmatic and operations functions of Stratolaunch, including oversight of the carrier aircraft, conversion of the carrier aircraft into a mobile launch platform, and leadership for many of the business functions.

The vision of Stratolaunch is ‘Breaking Barriers’ and their mission is advancing high speed technology through innovative design, manufacturing and operation of world-class aerospace vehicles.

Krevor’s opening slide showed that the company also stands on high values: Deliver today; Grow for tomorrow and Accuracy and Integrity always.

“What we are offering is flight test services for the hypersonics community,” said Krevor. “We have transitioned ownership under Mr. Paul Allen and our current owner is Cerberus Capital Management, a private equity group,”

“We are fully funded to bring hypersonic flight test to the aerospace community,” Krevor said. “We have transitioned our headquarters from Seattle down to Mojave Air and Space Port.”

The aircraft features a twin-fuselage design and the longest wingspan ever flown, at 385 feet, surpassing the Hughes H-4 Hercules flying boat of 321 feet. The flight crew is in the right fuselage and the flight data systems are located in the left fuselage.

Stratolaunch, the multi-vehicle launch platform, will carry a 550,000-pound payload and has a 1,300,000-pound maximum takeoff weight.

Stratolaunch Carrier Aircraft Development History: Mason Hutchinson, Lead Engineer — An Insider’s Perspective

Mason Hutchison started his engineering career at Ball Aerospace, working on the Airborne Laser program, focusing on material interaction of laser engagement. It was a lifelong interest in experimental aviation design that later drew him to Scaled Composites. It is there that he gained experience in design, build, and testing of the SpaceShipTwo feather deployment system. Soon after, he completed the White Knight Two landing gear design and release system and saw them through flight test. From there, Mason led the Flight Controls design team on the Stratolaunch aircraft. Currently, Mason works for Stratolaunch as the lead engineer for the Release System for the Talon hypersonic unmanned system.

“I started my career with an adventure through model aviation and I’ve been a model aviator my entire life; and as a matter of fact Stratolaunch enabled me to appear in my favorite magazine, which is Model Aviation magazine, in 2020.

“I came aboard to design the mechanical flight control system and I have been here ever since the first roll of carbon fiber fabric showed up to build the airplane, all the way through to today,” Hutchinson said. “So, I have been present for each of the two flights, and involved with the design and build of the airplane every single month of its progress.

“I am a lifelong aviator and got my roots working in Mojave at Scaled Composites and have a lot of experience working with landing gears and systems, so I am a systems designer” he said.

“I am passionate about the Stratolaunch aircraft,” Hutchinson said. “Being an engineer here, I enjoy getting to work on all areas of the program.

“This is the Model 351 Stratolaunch Carrier Aircraft originally built by Scaled Composites. Although we are no longer part of Scaled Composites, Stratolaunch is a stand-alone company and this is known as the Stratolaunch Aircraft and our current mission is to offer high speed flight test services that Zach just mentioned.”

Hutchinson described the purpose of the carrier aircraft by saying, “The Stratolaunch carrier aircraft, from the start of conceptual sketches until the first flight, was to carry rockets to an advantageous altitude that would allow for launching from flexible locations.”

Showing a slide that described separation of rocket from Stratolaunch, Hutchinson said, “Understanding the safe separation and careful mitigation of associated risks for separation is where Stratolaunch shines.”

Big Launcher History

“This is an old idea that has been around for a long time. In the 1940s, the original H-4 Hercules Hughes concept looks familiar. Then in the 1960s, they needed an aircraft to carry the Space Shuttle,” Hutchinson explained, showing a photo of a twin hull C-5 concept that Lockheed had considered for that task. The low wing design of the top launch 747 design was favored over the high wing design of the C-5 concept mostly because of the number of mods that were needed.

Hutchinson showed a sketch of another offering, moving the wing of the 747 to a high wing model with two fuselages and shuttle carried underneath, which was also considered. Again, the extensive modifications that would be needed was the obvious obstacle to this concept.

He showed an image of the Conroy Virtus ultra heavy cargo lifter that he had researched on the Internet, with a ‘Hershey Bar’ wing which he explained was theoretically easy to build and better for range, but this was a twin fuselage which was derived from B-52s and used the jet engines off of the B-52. “Look at that wing configuration, he’s on to something here,” said Hutchinson.

Configuration evolution

“Given the history of launchers, the evolution of this concept and this design from Burt Rutan’s sketches, all the way up to today, the configuration that we are flying actually takes an interesting path,” said Hutchinson. “I was actually able to gather some sketches that were made, casual ideas that were just archived over the years.”

He showed a Burt Rutan sketch that was from April 1990. “It’s a doodle of a centrally loaded carrier with an offset pilot. This is the first manifestation of that offset pilot on this carrier configuration.”

“From the conceptual layout, from the very beginning, Burt begins considering the experience of the launch as an attractive feature that includes an observer station in the aircraft and in this case you can see observers in the right hand fuselage, just behind the crew. So, he is from the beginning seeing what that experience would be like.”

Another sketch showed the SpaceShipOne and carrier aircraft White Knight emerging in Burt’s drawings. Hutchinson explained that the concept really began to blossom when other engineers joined with Rutan to design a carrier aircraft that would reuse the major airline systems and components. He described it as, “The winning combination of this idea of this configuration.”

In August 2000 they had a 3-D model with more people working on the concept. He showed another pencil sketch that Rutan had drawn and said, “It’s not that Burt is simply a great aircraft designer; his approach to design is mission-centric. He identifies ways in which he can utilize each design to fulfill the mission. It’s not uniqueness for the sake of being unique, it is uniqueness to achieve a goal.”

A Bronco-type tail was considered before, with the cockpit placement at the top of the fin, but it was actually heavier than the two-cruciform tail configuration that was finally decided on. A cruciform tail is an aircraft empennage configuration which, when viewed from the aircraft’s front or rear, looks much like a cross.

Hutchinson said, “I liked the idea of the cockpit placement on top of the fin, because they were considering having an emergency egress system where the crew would slide through the vertical fin and out the bottom somehow. It was completely unusual and out of the box thinking.”

Stratolaunch carrier aircraft

During Hutchinson’s presentation, he reiterated how impressed he was that the donor 747 aircraft parts and systems were able to be reused in the building of Stratolaunch.

Not only the landing gear and engines, but the cockpit windows were placed into the two fuselages of Stratolaunch. Many other parts were harvested from the 747 as well, including the yokes, rudder pedals, control seat rails, cockpit cabin floors, and instrument panels.

As he concluded his presentation, Hutchinson asked the question, “So, how big is it? 385-foot wingspan, 280-feet long and max takeoff design weight is intended to be 1.3-million pounds. We haven’t tested to that point yet, but we are using the airplane with the intent to build up to carry more weight eventually.

“We think that we also have the world’s largest single aircraft component, which would be the wing spars which are only partial span. They go from the dihedral break or planform break to the other planform break. They are approximately 250-feet long each. We have not been informed of any other piece larger than this. We think that is the largest aircraft component ever built.” He asked the audience to let him know if there was any other aircraft component that might be larger.

Hutchinson showed a drawing that illustrated the systems complexity of Stratolaunch. “There are four hydraulic systems, almost a quarter statute mile of control cable. Each engine has an air-driven hydraulic pump, an engine-driven hydraulic pump and an electric hydraulic driven pump, together making more than two-hundred total horsepower of hydraulic service to the flight controls, the landing gear, and the braking systems. Each engine provides electrical power that is pumped into two massive power bus systems that meet at the center wing.”

“It is not possible to access the fuselage or convey through the wing while in flight,” Hutchinson said. “The pilots are sequestered only to the pressure vessel of the right forward cabin and are unable to actually transfer into the fuselage while in flight. But, that being said, you cannot walk through the wing either.”

Hutchinson showed photos of the Talon One unmanned autonomous, Mach-6 rocket that will be launched from a Stratolaunch carrier aircraft in the future.

“The payoff in this job is I get to work with my best friends, and every single day it doesn’t feel like a job, it is an experience,” Hutchinson concluded.

First Flight — April 13, 2019

Col. Evan “Ivan” Thomas is the director of Flight Operations for Stratolaunch, LLC and he described how the crew sits in the right fuselage and described where the aircraft carries most of its weight.

“The fuel tanks are all outboard of the fuselages in the wing. There are no fuel tanks in the fuselages, they are basically hollow tubes,” Thomas said. “If you want a physical analogy, it’s a bit like a shopping cart with a heavy barbell strapped to the top.

“It’s got a lot of inertia and weight out in the wings and that comes into play later in the flight.

“For our first flight, all of our flight controls were mechanically-signaled cables, cables running from the right cabin all the way out to both empennages, all of the four elevators, four rudders, both banks of ailerons on both sides, so a lot of cable,” said Thomas.

“First flight had one objective, and that was to land safely,” Thomas said. “The risks we looked at for the first flight was runway departure on landing was a big one, but also stability and control, or the possibility of pilot induced oscillations. Also because it is a very large carbon structure, so the possibilities of getting some odd structural vibrations, bio mechanical feedback between us and the control inputs and then pilot conceptual concerns of sitting there in the right fuselage way out front.

“Ultimately the first flight was about handling to precisely control the aircraft to a stable, centered landing,” said Thomas. “The big landing challenges — we have a 200-foot wide runway at Mojave, and it is 114-feet from the outside of one set of landing gear to the outside of the other set, so we are pretty wide there, which gives us 43-feet on either side to play with.

“We come into the flare a bit nose down, much like a B-52, so that concern was that we didn’t want to land nose gear first and start porpoising,” he stated. He showed a photo that was taken from space of Stratolaunch on Runway 30 at Mojave.

First Flight Profile

“We started with handling qualities evaluation basics, which is four primary steps. First we want to do thorough ground test so you understand your system. Then when you are airborne you want to do some open loop responses and see what the aircraft’s natural response is to inputs and some basic capture tasks,” Thomas said.

On the first flight profile, they were to take off with no flaps, climb to 15,000 feet at 150 knots, and do a few pitch, yaw and roll maneuvers to check the handling qualities. Then during the flight, one of the big test points was to check the flaps. The flaps have two settings, up or full down 70-degrees, which makes them act as flaps or speed brakes.

Thomas described an item in the flight profile, a simulated landing that would be done at altitude. He said, “When we looked at doing the roll authority maneuvers, we were doing them essentially feet on the floor with some coordination. We realized there was potential to build sideslip which we had not looked at before.” As they kept looking at different possibilities, their flight profile list changed over time.

Before the first flight, Thomas told how the simulator was essential in the preparation for actual flight. They also got a surrogate aircraft, the Calspan VSS (Variable Stability System) Learjet with matched feel and Roc-like dynamics to do touch and go’s, giving great in-flight training. They conducted in-flight rehearsals of the Stratolaunch flight profile that sharpened their handling qualities and observation skills.

“It sounds like a cliché to say that our first flight was just like being in the simulator, but it almost was,” said Thomas. “We did find that we had a larger than predicted yaw due to roll.”

Innovations for First Flight

Thomas said, “We had a hot mic between the crew and the control room in both directions, and hot mic reception in the chase aircraft so they were able to completely keep up with what we were doing with the test cards.

“We did not pressurize the fuselage on the first flight and in fact, we ended up going with a fabric cabin door which sounded kinda crazy when an engineer first proposed it, but in actuality, it worked great,” said Thomas.

“The biggest innovation was designing, building, testing and then flying a 385-foot wingspan, composite, complex six-engine aircraft,” Thomas concluded.

Second Flight — April 2021

Thomas listed some changes that were made for the second flight of Stratolaunch, which included: new outboard aileron control system; new yaw control augmentation system; runway alignment display for landing and flutter instrumentation.

The outboard ailerons were converted to command-by-wire with direct control law. “We added a yaw augmentation system in parallel with mechanical yaw signals,” said Thomas. “We also converted all of the purely steel cable loops to hybrid steel and carbon configuration.

“Our second flight results, all systems again performed really well, complex as they are,” Thomas said. “It really is amazing that we got two flights on this airplane with virtually no significant write-ups for maintenance.

“We had a better lineup with the runway with the new runway alignment device and we made a better landing, which made me very happy” said Thomas.

“On the second landing we were a little bit longer on the lineup,” said Thomas. He showed a video taken from the center wing. He said, “As you watch this video, you can see the underlying, very slow yaw, it’s only a half of a degree to a degree, but it’s very hard for the pilots to suppress that and stop it. The bank is changing as I try to adjust the lateral error as we come in to the runway and make those fine corrections.”

Thomas is responsible for safe and effective flight test and operational use of the Stratolaunch carrier aircraft and other company aircraft, and ensuring readiness and compliance for all flight crew.

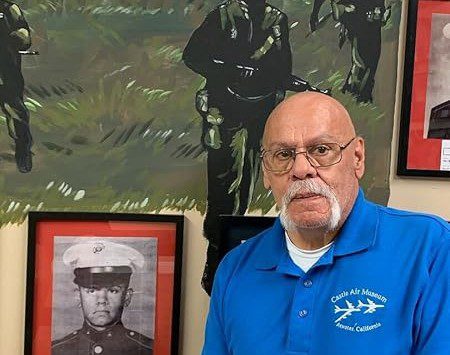

He was raised in Southern California, and pursued his dream of flying by attending the United States Air Force Academy, graduating in 1986 with a Bachelor of Science degree in Astronautical Engineering. After earning his Air Force pilot wings, Thomas completed two operational tours flying the F-16, including leading 52 combat missions over Iraq and occupied Kuwait, highlighted by the rescue of an encircled Special Forces team. In 1994 he was a pilot on the Overall Top Team at the U.S. Air Forces ‘William Tell’ Air-to-Air Weapons Meet.