On a ranch in Montana, the owner watched his cattle graze for decades from the comfort of his dining room table with his wife. Out that same window, past the cattle, is a small, fenced area containing a simple looking concrete slab with just a few small structures around it.

Every once in a while, the owners would bring up that site but never really felt the day would come that the small area on their ranch could produce the destruction of an entire city in a far-off land.

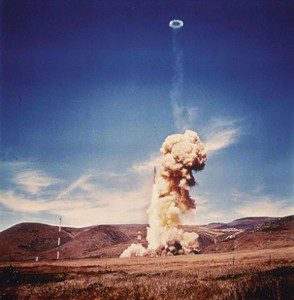

As the missile silo sat at the ready since the 1950s, the husband and wife always wondered what the day would look like when the earth rumbled, and smoke would blast into the air. Smoke from an open hatch would be followed by a missile climbing into the sky over their home. Prayers and a trip to the basement would be all they could do, as the world finally found out just how vulnerable humanity is.

For generations across America, communities lived in silent service with the United States Air Force as their neighbors, never realizing just how special these individuals were. They are asked to perform a service keeping the world in check, while living a life and working in the shadows with great responsibility.

For many across our country, the Air Force is all about the cutting-edge aircraft and the men and women who fly, design and maintain them. Citizens are always lining up to for autographs, pictures, and the stories of those magnificent men (and women) in their flying machines. But there is an entire aspect of the Air Force that never would get that type of community outreach. They now have their own service branch, and respectfully so — U.S. Space Force.

I would like to share some information about those Airmen with a missile logo on their uniform pocket; what it was like going to your duty station and serving your country without fanfare or notoriety, as you performed a task that was not filled with the excitement of flying. It was a trip up and down an elevator with long hours of drills, systems checks and constant maintenance needing to be done while not seeing the outside world for 40-hour shifts. Always wondering: Would the world still be there someday at the top of that elevator if they were ever charged with executing their one mission of a missile launch?

Early on, in the late 1950s, different missiles and missions determind the size and composition of the crews at the missile sites.

In the early days, SAC had 1,054 silos operational, and needed 900 new crewmen per year to crew them. Initially, SAC pulled older aviators to man the ICBM silos. As time went on, however, many of these initial crews headed for combat in Southeast Asia, and SAC started recruiting directly from ROTC programs and the Air Force Academy. Because of this effort, the average age of a missileer in the 1970s was between 22 and 30 years old, and most had no flying experience at all.

For most people, learning that these missile crews were under 30 years of age, it brings into focus just how responsible those young men and eventually women were who sat at the consoles of mass destruction.

What were the actual requirements to be selected for the missile programs? Here is what it took to be considered, and what a regular shift would look like to a “missileer.”

According to the www.themilitarystandard.com, in an entry titled Life At The Missile Sites, “Each candidate underwent extensive medical and psychological evaluation by SAC’s Human Reliability Program. After certification, training consisted of a three-step process. First, the candidate attended an Air Training Command school for familiarization with the weapon system. Potential Titan crewmen were sent to train at Sheppard AFB in Texas while Minuteman candidates went to school at Chanute AFB in Illinois. Next, the candidate was assigned to the 1st Strategic Aerospace Division at Vandenberg AFB, Calif., for operational training. Finally, the prospective crewman arrived at his assigned wing for familiarization with conditions unique to that area.

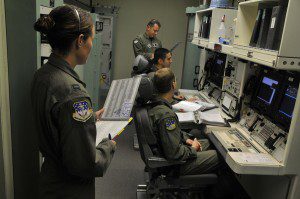

“Once placed on the duty rotation schedule for a Minuteman missile wing, a two-man crew averaged five tours per month of 36 to 40 hours per tour. Travel time to and from the silo could be considerable. For example, some silos at Minot AFB in North Dakota required a trip of 150 miles. During the 36-hour shift, the two-man crew stood two 12-hour shifts in the underground launch control center, broken up by a 12-hour on-site rest period while another crew stood watch.

“While on duty the crew commander and his deputy spent much of their time conducting frequent status checks of the missiles and their support systems. Duty in a missile silo was demanding.”

As I said before, the missileers endured a lack of respect, and the Air Force and SAC had to find way to overcome recruitment, retainment and sustainably issues as, early in the program, SAC encountered morale problems.

Even as SAC was recruiting from the ROTC programs and the Academy, morale was still an issue. Many officers chose to leave the Air Force after their initial service commitment because, while they understood the importance of the mission, there was resentment at the way they perceived their aircrew peers looked down on them.

To counter this, and to recruit high-quality officers to the career, SAC started offering advanced degree programs.

“As early as December 1961, SAC had expressed the view that a good educational program would permit missile crews to put the long hours of alert duty to profitable use,” according to www.themilitarystandard.com. “However, the demanding maintenance requirements of the first-generation missiles left little extra time for study.”

As time went on, missile designs improved, and the introduction of the solid-propellant Minuteman meant fewer men were needed below ground.

“In contrast to a 12-missile Atlas F Squadron, which always kept 60 men underground, a 150-missile Minuteman wing could do the same job with 30, as each two-man crew had responsibility for 10 missiles,” says www.themilitarystandard.com.

It wasn’t until 1978 that women joined men on missile crew duty for the first time.

Even with fewer crew members, responsible for more missiles, the crews had more free time on their hands than their predecessors. They still had to review procedures, prepare for inspections, or run drills, but they still had more time.

In 1967, at Vandenberg Air Force Base, Calif., the Air Force instituted an annual missile crew competition, eventually known as “Olympic Arena,” to enhance and maintain crew morale.

Now you understand a bit more about our unseen heroes, I will close this issue looking forward to our next issue when I will share a personal story about a family member of mine who made an Air Force career as a missileer and how a very dangerous mission with high stress levels could have its more lighthearted moments.

Until next time, think about these same men and women out there right now serving in a manner that often gets overlooked, and pray the day never comes when their mission becomes a reality.

Until then, Bob out!

See Part II: The missile men of the USAF