Marine Corps Maj. Gen. James Everett Livingston became a trusted commander during his more than three decades in the service. He learned leadership skills early in his career and put them to good use in 1968 when he helped liberate a Vietnamese village and save stranded Marines. For that, he earned the Medal of Honor.

Livingston was born on Jan. 12, 1940, in rural Towns, Ga. He and his brother, Donald, were raised on a 3,000-acre farm which they helped their parents, Myret and Ruth Livingston, work as much as possible.

Livingston said he was one of 26 students who graduated from Lumber City High School in 1957. He attended the Military College of Georgia, the current-day University of North Georgia, and was a member of the school’s renowned Corps of Cadets before transferring to Auburn University.

Livingston received his draft notice during his junior year of college. He said he nearly joined the Army before meeting a Marine Corps recruiter who convinced him to join the Marines instead. So, in June 1962, after graduating with a civil engineering degree, Livingston was commissioned as a Marine second lieutenant. He initially planned to do a three-year stint before returning to civilian life.

Not long after finishing basic school, Livingston was sent to Okinawa with a transplacement battalion ó meaning instead of relieving individual Marines from deployment, the Corps relieved entire battalions to retain unity and efficiency. For about 13 months during 1963 and 1964, Livingston served either off the coast of Vietnam or in the embattled country for short periods of time.

After returning to the U.S., Livingston was given the opportunity to train new recruits at Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island, S.C. He said he enjoyed that so much that he changed his mind about leaving the service and decided to reenlist. While he was stationed at Parris Island, he also met his wife, Sara. They went on to have two daughters, Melissa and Kimberly, the latter of whom attended the Naval Academy later in life.

Livingston was promoted to captain in 1966. He served as the commanding officer of the Marine detachment aboard the aircraft carrier USS Wasp before deploying on his second tour of duty to Vietnam in August 1967.

By late April 1968, Livingston was serving as the commanding officer of Company E of the 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines, 9th Marine Amphibious Brigade. The battalion was positioned to the east of Dong Ha Combat Base, a strategic post used to move supplies to other crucial areas.

On May 1, 1968, the nearby village of Dai Do was taken over by enemy forces about 10,000 strong in an attack that left a Marine company isolated from the rest of the battalion. To help those stranded Marines, Livingston’s company was ordered to win back the heavily fortified village.

On May 2, Livingston led his men across about 500 meters of open-air rice paddies that left them vulnerable to intense enemy fire. Livingston’s men then fearlessly began their assault against enemy emplacements within the village.

Livingston himself moved to the points of heaviest resistance so he could encourage his Marines, direct their fire and keep up the momentum of the attack. He was wounded twice by grenade fragments but refused medical attention.

Together, Livingston and his men destroyed more than 100 enemy bunkers and drove the rest of the enemy from their positions in the village, which helped relieve the pressure on the Marine company that had been isolated.

While Livingston said they killed up to 400 enemy soldiers during the attack, U.S. forces had suffered, too.

“I went into the fight with about 180 Marines,” he said during a Library of Congress Veterans History Project interview. “After that stage of the fight, I only had about 35 Marines who were still walking.”

The two companies consolidated their positions and evacuated their casualties. As they did so, a third company passed through their area and launched an attack on an adjacent village called Dinh To; however, their efforts were thwarted by a counterattack.

Livingston quickly assessed the situation and, without orders, maneuvered his company forward to join forces with the third company, who were engaged in intense fighting. Together, the combined U.S. forces were able to halt the enemy’s counterattack.

During this part of the fight, Livingston was wounded a third time and could no longer walk.

“All the kids saw me go down,” he said, referring to the 18- and 19-year-old Marines he commanded. “We’d been really slugging it out and taking a lot of casualties. Basically, I told the kids to get out of there, because we were getting surrounded, and leave me there ó I’d take care of the bad guys up to the point I could no longer take care of the bad guys.”

According to Livingston’s citation, he remained in the dangerously exposed area and supervised the evacuation of casualties while deploying his able-bodied men moved to more tenable positions. It was only when he was assured of their safety that he allowed himself to be taken to shelter.

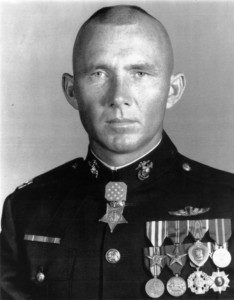

A lot of Marines were lost during the Battle of Dai Do, but Livingston was one of the lucky ones. He was evacuated by helicopter to Hawaii and spent several months in a hospital. When he got back to his battalion in Okinawa, he learned that he and another Marine company commander, Capt. Jay Vargas, had been nominated for the Navy Cross for their actions at Dai Do. Later, however, both nominations were upgraded to Medals of Honor.

Livingston received the nation’s highest military award for valor on May 14, 1970, from President Richard M. Nixon during a White House ceremony. His entire family was able to attend, including his infant daughter. A few other service members were also presented Medals of Honor that day.

“The MOH is the reflection of the experience I had in Vietnam, but most of all, it’s the reflection of the fine young Marines I wear it for,” Livingston said when he was asked what the medal means to him. “I try to wear it in remembrance of them.”

Livingston served as an instructor and then operations officer before returning to Vietnam in March 1975 to help with evacuation operations, including in Saigon.

He eventually earned a master’s degree in management from Webster University while continuing to work his way up the ladder. In the late 1980s, Livingston served as the deputy director for operations at the National Military Command Center in Washington, D.C. During Desert Storm, he commanded the Marine Air Ground Combat Center at Twentynine Palms, Calif., and developed the Desert Warfare Training Program. He went on to command the 1st Marine Expeditionary Brigade and then the 4th Marine Division.

By July 1992, then-Maj. Gen. Livingston assumed command of the more than 100,000 Marines in the newly created Marine Reserve Force based in Louisiana. He remained in that post through its reorganization in late 1994 when its title changed to the Marine Forces Reserve.

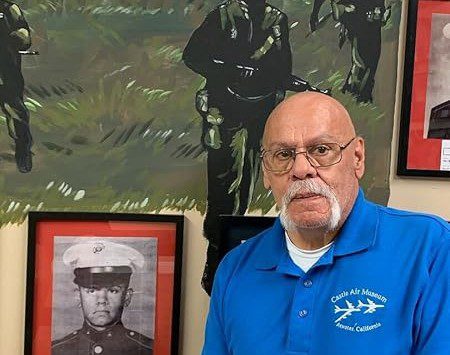

Livingston retired on Sept. 1, 1995, after a 33-year career. However, he has remained active in the military community. He wrote a book about his experiences, called “Noble Warrior,” and he continues to take part in military awareness campaigns and veterans’ events, including a recent Army Corps of Engineers leadership development program at his current hometown of Charleston, S.C.

Editor’s note: Medal of Honor Monday highlights Medal of Honor recipients who have earned the U.S. military’s highest medal for valor.