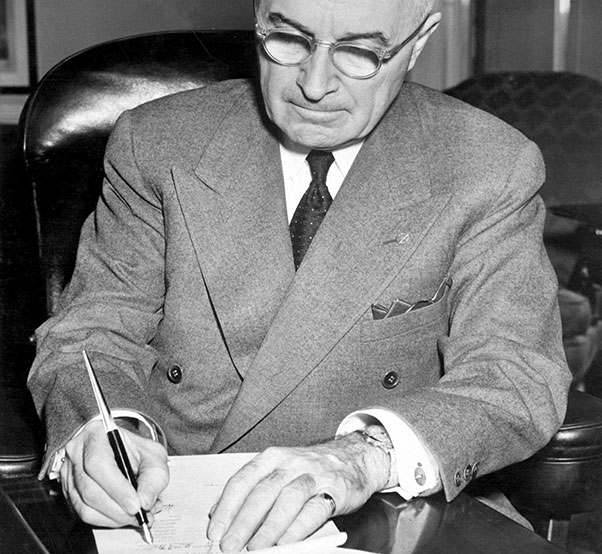

President Harry S. Truman signs the National Security Act of 1947 on Sept. 18, 1947, creating the U.S. Air Force as a separate service of the U.S. military.

With the stroke of a pen, President Harry S. Truman signed the National Security Act of 1947 on Sept. 18, 1947.

The Act created the National Military Establishment – later renamed the Department of Defense – and created the U.S. Air Force as a separate branch of the U.S. military.

The signing began a three-year transition period in which soldiers became airmen and army air fields became air force bases.

Before that, the responsibility for military aviation was divided between the U.S. Army for land-based operations and the U.S. Navy for sea-based operations.

And while we celebrate the 70th anniversary of the creation of the U.S. Air Force on Sept. 18, the history of U.S. military aviation can be traced back to 1907, when the U.S. Army created the Aeronautical Division, Signal Corps.

U.S. military aviation has changed over the years — from bi-planes during World War I to the modern jet fighter aircraft — but one thing remains constant, the motivation and resiliency of U.S. Airmen to protect and defend their home.

On Sept. 18, the U.S. Air Force will celebrate its 70th anniversary.

W. Stuart Symington, former Assistant Secretary of War for Air (1946-47) is shown taking the oath of office as Secretary of the Air Force from Chief Justice Fred Vinson. Left to right: Symington, Secretary of the Army Kenneth C. Royall; Secretary of Defense James N. Forrestal; Chief Justice Fred Vinson; and Secretary of the Navy John L. Sullivan.

U.S. Airmen around the world will celebrate — there will be birthday cake, and balls and many different kinds of celebrations. Wherever U.S. Airmen are based they will mark this important date.

And as we look back and honor the U.S. men and women who have made the U.S. Air Force the greatest air force in the world, we have no doubt that the Airmen of today will continue to build on the legacy their predecessors have provided them.

In this special issue of Aerotech News and Review, we mark this special anniversary with a look back at the past 70 years.

And so the staff of Aerotech News and Review want to take this opportunity to wish the U.S. Air Force a very ‘Happy Birthday!’

In the beginning: World War I

In 1917, upon the United States’ entry into World War I, the first major U.S. aviation combat force was created when an Air Service was formed as part of the American Expeditionary Force. Maj. Gen. Mason Patrick commanded the Air Service of the AEF; his deputy was Brig. Gen. Billy Mitchell.

These aviation units, some of which were trained in France, provided tactical support for the U.S. Army, especially during the Battle of Saint-Mihiel and the Meuse-Argonne offensives.

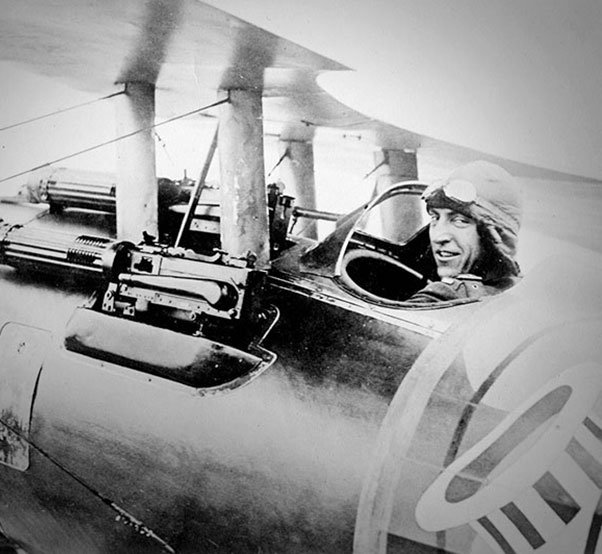

Capt. Edward Vernon Rickenbacker was an American fighter ace in World War I and Medal of Honor recipient. With 26 aerial victories, he was America’s most successful fighter ace in the war.

Concurrent with the creation of this combat force, the U.S. Army’s aviation establishment in the United States was removed from control of the Signal Corps and placed directly under the United States Secretary of War. An assistant secretary was created to direct the Army Air Service, which had dual responsibilities for development and procurement of aircraft, and raising and training of air units. With the end of the First World War, the AEF’s Air Service was dissolved and the Army Air Service in the United States largely demobilized.

In 1920, the Air Service became a branch of the Army and in 1926 was renamed the Army Air Corps. During this period, the Air Corps began experimenting with new techniques, including air-to-air refueling and the development of the B-9 and the Martin B-10, the first all-metal monoplane bombers, and new fighters.

During World War I, aviation technology developed rapidly; however, the Army’s reluctance to use the new technology began to make airmen think that as long as the Army controlled aviation, development would be stunted and a potentially valuable force neglected.

U.S. airmen in France, Oct. 2, 1918.

Air Corps senior officer Billy Mitchell began to campaign for Air Corps independence. But his campaign offended many and resulted in a court martial in 1925 that effectively ended his career. His followers, including future aviation leaders “Hap” Arnold and Carl Spaatz, saw the lack of public, congressional, and military support that Mitchell received and decided that America was not ready for an independent air force. Under the leadership of its chief of staff Mason Patrick and, later, Arnold, the Air Corps waited until the time to fight for independence arose again.

World War II: Air power comes of age

U.S. air power came of age during World War II.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt took the lead, calling for a vastly enlarged air force based on long-range strategic bombing. Organizationally it became largely independent in 1941, when the Army Air Corps became a part of the new U.S. Army Air Forces, and the GHQ Air Force was redesignated the subordinate Combat Command.

In the major reorganization of the Army by War Department Circular 59, effective March 9, 1942, the newly created Army Air Forces gained equal voice with the Army and Navy on the Joint Chiefs of Staff and complete autonomy from the Army Ground Forces and the Services of Supply.

The reorganization also eliminated both Combat Command and the Air Corps as organizations in favor of a streamlined system of commands and numbered air forces for decentralized management of the burgeoning Army Air Forces.

The reorganization merged all aviation elements of the former air arm into the Army Air Forces.

On April 18, 1942, the United States conducted an air raid on Tokyo and other locations in Japan. The raid was planned and led by Lt. Col. James “Jimmy” Doolittle, thus becoming known as the Doolittle Raid. Sixteen B-25 Mitchell bombers were launched from the USS Hornet – and following the raid, were supposed to land in China. Fifteen aircraft reached China, but they all crashed, while the 16th landed in Vladivostok in the Soviet Union.

Although the Air Corps still legally existed as an Army branch, the position and Office of the Chief of the Air Corps was dissolved. However, people in and out of AAF who remembered the prewar designation often used the term “Air Corps” informally, as did the media.

Maj. Gen. Carl A. Spaatz took command of the Eighth Air Force in London in 1942; with Brig. Gen. Ira Eaker as second in command, he supervised the strategic bombing campaign.

In late 1943, Spaatz was made commander of the new U.S. Strategic Air Forces, reporting directly to the Combined Chiefs of Staff.

Spaatz began daylight bombing operations using the prewar doctrine of flying bombers in close formations, relying on their combined defensive firepower for protection from attacking enemy aircraft rather than supporting fighter escorts. The doctrine proved flawed when deep-penetration missions beyond the range of escort fighters were attempted, because German fighter planes overwhelmed U.S. formations, shooting down bombers in excess of “acceptable” loss rates, especially in combination with the vast number of flak anti-aircraft batteries defending Germany’s major targets. American fliers took heavy casualties during raids on the oil refineries of Ploesti, Romania, and the ball-bearing factories at Schweinfurt and Regensburg, Germany. It was the loss in crews and not materiel that brought about a pullback from the strategic offensive in the autumn of 1943.

The Eighth Air Force had attempted to use both the P-47 and P-38 as escorts, but while the Thunderbolt was a capable dog-fighter it lacked the range, even with the addition of drop tanks to extend its range and the Lightning proved mechanically unreliable in the frigid altitudes at which the missions were fought.

Bomber protection was greatly improved after the introduction of North American P-51 Mustang fighters in Europe. With its built-in extended range and competitive or superior performance characteristics in comparison to all existing German piston-engined fighters, the Mustang was an immediately available solution to the crisis.

In January 1944, the Eighth Air Force obtained priority in equipping its groups so that ultimately 14 of its 15 groups fielded Mustangs. P-51 escorts began operations in February 1944 and increased their numbers rapidly, so that the Luftwaffe suffered increasing fighter losses in aerial engagements beginning with Big Week in early 1944. Allied fighters were also granted free rein in attacking German fighter airfields, both in pre-planned missions and while returning to base from escort duties, and the major Luftwaffe threat against Allied bombers was severely diminished by D-Day.

In the Pacific Theater of Operations, the AAF provided major tactical support under Gen. George Kenney to Douglas MacArthur in the Southwest Pacific Theater.

Kenney’s pilots invented the skip-bombing technique against Japanese ships. Kenney’s forces claimed destruction of 11,900 Japanese planes and 1.7 million tons of shipping.

The first development and sustained implementation of airlift by American air forces occurred between May 1942 and November 1945 as hundreds of transports flew more than half a million tons of supplies from India to China over the Hump.

The AAF created the 20th Air Force to employ long-range B-29 Superfortress bombers in strategic attacks on Japanese cities.

The use of forward bases in China (needed to be able to reach Japan by the heavily laden B-29s) was ineffective because of the difficulty in logistically supporting the bases entirely by air from its main bases in India, and because of a persistent threat against the Chinese airfields by the Japanese army.

After the Mariana Islands were captured in mid-1944, providing locations for air bases that could be supplied by sea, Arnold moved all B-29 operations there by April 1945 and made Gen. Curtis LeMay his bomber commander, reporting directly to Arnold.

The Enola Gay is a Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber, named for Enola Gay Tibbets, the mother of the pilot, Col. Paul Tibbets, who selected the aircraft while it was still on the assembly line. On Aug. 6, 1945, during the final stages of World War II, it became the first aircraft to drop an atomic bomb. The bomb, code-named “Little Boy”, was targeted at the city of Hiroshima, Japan. Enola Gay participated in the second atomic attack as the weather reconnaissance aircraft for the primary target of Kokura. Clouds and drifting smoke resulted in a secondary target, Nagasaki, being bombed instead.

LeMay reasoned that the Japanese economy, much of which was cottage industry in dense urban areas where manufacturing and assembly plants were also located, was particularly vulnerable to area attack and abandoned inefficient high-altitude precision bombing in favor of low-level incendiary bombings aimed at destroying large urban areas.

On the night of March 9–10, 1945, the bombing of Tokyo and the resulting conflagration resulted in the death of more than 100,000 persons. About 350,000 people died in 66 other Japanese cities as a result of this shift to incendiary bombing. At the same time, the B-29 was also employed in widespread mining of Japanese harbors and sea lanes.

In early August 1945, the 20th Air Force conducted atomic bomb attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in response to Japan’s rejection of the Potsdam Declaration which outlined the terms of surrender for Japan.

Both cities were destroyed with enormous loss of life and psychological shock. On Aug. 15, Emperor Hirohito announced the surrender of Japan, stating:

“Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is indeed incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should We continue to fight, it would not only result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization. Such being the case, how are We to save the millions of Our subjects; or to atone Ourselves before the hallowed spirits of Our Imperial Ancestors? This is the reason why We have ordered the acceptance of the provisions of the Joint Declaration of the Powers.”

The Air Force matures, and the Cold War begins

In practice, the Army Air Forces became virtually independent of the Army during World War II, but its leaders wanted formal independence.

In November 1945, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower became Army Chief of Staff, while Gen. Carl Spaatz began to assume the duties of Commanding General, Army Air Forces, in anticipation of Gen. Hap Arnold’s announced retirement.

One of Eisenhower’s first actions was to appoint a board of officers, headed by Lt. Gen. William H. Simpson, to prepare a definitive plan for the reorganization of the Army and the Air Force that could be affected without enabling legislation and would provide for the separation of the Air Force from the Army.

On Jan. 29, 1946, Eisenhower and Spaatz agreed on an Air Force organization composed of the Strategic Air Command, the Air Defense Command, the Tactical Air Command, the Air Transport Command and the supporting Air Technical Service Command, Air Training Command, the Air University, and the Air Force Center.

West Berliners watch as a U.S. cargo plane delivers desperately needed supplies during the Berlin Airlift.

Over the continuing objections of the Navy, the United States Department of the Air Force was created by the National Security Act of 1947. That act became effective Sept. 18, 1947, when the first secretary of the Air Force, Stuart Symington, took office. In 1948, the service chiefs agreed on usage of air assets under the Key West Agreement.

The newly formed U.S. Air Force quickly began establishing its own identity.

Army Air Fields were renamed Air Force Bases and personnel were soon being issued new uniforms with new rank insignia. Once the new Air Force was free of Army domination, its first job was to discard the old and inadequate ground army organizational structure. This was the “Base Plan” where the combat group commander reported to the base commander, who was often “regular Army,” with no flying experience.

Spaatz established a new policy: “No tactical commander should be subordinate to the station commander.”

This resulted in a search for a better arrangement.

The commander of the 15th Air Force, Maj. Gen. Charles Born, proposed the Provisional Wing Plan, which basically reversed the situation and put the wing commander over the base commander. The U.S. Air Force basic organizational unit became the base-wing.

Under this plan, the base support functions — supply, base operations, transportation, security, and medical — were assigned to squadrons, usually commanded by a major or lieutenant colonel. All of these squadrons were assigned to a combat support group, commanded by a base commander, usually a colonel.

Combat fighter or bomber squadrons were assigned to the combat group, a holdover from the U.S. Army Air Force group. All of these groups, both combat and combat support, were in turn assigned to the wing, commanded by a wing commander.

This way the wing commander commanded both the combat operational elements on the base as well as the non-operational elements. The wing commander was an experienced air combat leader, usually a colonel or brigadier general.

All of the hierarchical organizations carried the same numerical designation. In this manner, for example, the 28th became the designation for the Wing and all the subordinate groups and squadrons beneath it. As a result, the base and the wing became one and the same unit.

On June 6, 1952, the legacy combat groups were inactivated and the operational Combat Squadrons were assigned directly to the Wing. The World War II history, lineage and honors of the combat group were bestowed on the Wing upon its inactivation.

The USAAF wing then was redesignated as an Air Division, which was commanded by a brigadier general or higher, who usually, but not always, commanded two or more wings on a single base. Numbered Air Forces commanded both air divisions or wings directly, and the numbered air force was under the major command — Strategic Air Command, Tactical Air Command, etc.

After World War II, relations between the United States and the Soviet Union began to deteriorate, and the period in history known as the Cold War began.

The United States entered an arms race with the Soviet Union and competition aimed at increasing each nation’s influence throughout the world. In response, the United States expanded its military presence throughout the world.

Planes are unloaded at Tempelhof airport during the Berlin Airlift.

The U.S. Air Force opened air bases throughout Europe, and later in Japan and South Korea. The United States also built air bases on the British overseas territories of British Indian Ocean Territory and Ascension Island in the South Atlantic.

The first test for the U.S. Air Force during the Cold War came in 1948, when Communist authorities in East Germany cut off road and air transportation to West Berlin.

The Air Force, along with the Royal Air Force and Commonwealth air forces, supplied the city during the Berlin airlift under Operation Vittles, using C-54 Skymasters. The efforts of these air forces saved the city from starvation and forced the Soviets to back down in their blockade.

Conflict over post-war military administration, especially with regard to the roles and missions to be assigned to the Air Force and the U.S. Navy, led to an episode called the “Revolt of the Admirals” in the late 1940s, in which high-ranking Navy officers argued the case for carrier-based aircraft rather than strategic bombers.

In 1947, the Air Force began Project Sign, a study of unidentified flying objects which would be twice revived (first as Project Grudge and finally as Project Blue Book) and which would last until 1969.

In 1948 the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act gave women permanent status in the Regular and Reserve forces of the Air Force. And on July 8, 1948, Esther McGowin Blake became the first woman in the Air Force, enlisting the first minute of the first hour of the first day regular Air Force duty was authorized for women.

The Korean War years

During the Korean War, which began in June 1950, the Far East Air Forces were among the first units to respond to the invasion by North Korea, but quickly lost its main airbase at Kimpo, South Korea.

F-86 Sabres with their 51st Fighter Interceptor Wing “Checkertails” are readied for combat during the Korean War at Suwon Air Base, South Korea.

Forced to provide close air support to the defenders of the Pusan pocket from bases in Japan, the FEAF also conducted a strategic bombing campaign against North Korea’s war-making potential simultaneously.

Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s landing at Inchon in September 1950 enabled the FEAF to return to Korea and develop bases from which they supported MacArthur’s drive to the Korean-Chinese border.

When the Chinese People’s Liberation Army attacked in December 1950, the Air Force provided tactical air support. The introduction of Soviet-made MiG-15 jet fighters caused problems for the B-29s used to bomb North Korea, but the Air Force countered the MiGs with its new F-86 Sabre jet fighters.

Although both air superiority and close air support missions were successful, a lengthy attempt to interdict communist supply lines by air attack failed and was replaced by a systematic campaign to inflict as much economic cost to North Korea and the Chinese forces as long as war persisted, including attacks on the capital city of Pyongyang and against the North Korean hydroelectric system.

Left side view of an RF-4C Phantom II with auxiliary fuel tanks in flight August 1968. The aircraft was assigned to the 192nd Tactical Reconnaissance Group, Nevada Air National Guard.

Vietnam War: Air power matures

The U.S. Air Force was heavily deployed during the Vietnam War.

The first bombing raids against North Vietnam occurred in 1964, following the Gulf of Tonkin Incident.

In March 1965, a sustained bombing campaign began, code-named Operation Rolling Thunder. This campaign’s purpose was to destroy the will of the North Vietnamese to fight, destroy industrial bases and air defenses, and to stop the flow of men and supplies down the Ho Chi Minh Trail, while forcing North Vietnam into peace negotiations.

Newly freed prisoners of war celebrate as their C-141A aircraft lifts off from Hanoi, North Vietnam, on Feb. 12, 1973, during Operation Homecoming. The mission included 54 C-141 flights between Feb. 12 and April 4, 1973, returning 591 POWs to American soil.

The Air Force dropped more bombs in all combat operations in Vietnam during the period 1965–68 than it did during World War II, and the Rolling Thunder campaign lasted until the U.S. presidential election of 1968. Except for heavily damaging the North Vietnamese economy and infrastructure, Rolling Thunder failed in its political and strategic goals.

The Air Force also played a critical role in defeating the Easter Offensive of 1972.

The rapid redeployment of fighters, bombers and attack aircraft helped the South Vietnamese Army repel the invasion. Operation Linebacker demonstrated to both the North and South Vietnamese that even without significant U.S. Army ground forces, the United States could still influence the war. The air war for the United States ended with Operation Linebacker II, also known as the “Christmas Bombings.” These helped to finalize the Paris peace negotiations.

Capt. Charles B. DeBellevue, Vietnam Ace F-4D Phantom at Udorn AB, Thailand. As a captain, DeBellevue became the first non-pilot ace and the leading ace in the U.S. Air Force during the Vietnam War. He was an F-4 weapon system officer with the 555th Tactical Fighter Squadron. Later in his career, DeBellevue was base commander at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif.

The insurgent nature of combat operations early in the war, and the necessity of interdicting the North Vietnamese regular army and its supply lines in third-party countries of Southeast Asia led to the development of a significant special operations capability within the Air Force.

Provisional and experimental concepts such as air commandos and aerial gunships, tactical missions such as the partially successful Operation Ivory Coast, deep inside enemy territory, and a dedicated Combat Search and Rescue mission resulted in development of operational doctrines, units, and equipment.

When the Vietnam War came to an end, the U.S. Air Force was responsible for flying newly freed POWs from Hanoi, North Vietnam, to the United States. Between Feb. 12 and April 4, 1973, the Air Force flew 54 C-141 flights as part of Operation Homecoming.

F-16A Fighting Falcon, F-15C Eagle and F-15E Strike Eagle fighter aircraft fly over burning oil field sites in Kuwait during Operation Desert Storm.

Post-Vietnam to the Global War on Terror

The Air Force modernized its tactical air forces in the late 1970s with the introduction of the F-15, A-10, and F-16 fighters, and the implementation of realistic training scenarios under the aegis of Red Flag.

In turn, it also upgraded the equipment and capabilities of its Air Reserve Components by the equipping of both the Air National Guard and Air Force Reserve with first-line aircraft.

Expanding its force structure in the 1980s to 40 fighter wings and drawing further on the lessons of the Vietnam War, the Air Force also dedicated units and aircraft to Electronic Warfare and the Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses.

The humiliating failure in April 1980 of the Operation Eagle Claw rescue mission in Iran resulted directly in an increased U.S. Air Force emphasis on participation in the doctrine, equipment, personnel, and planning of Joint Special Operations.

The Air Force provided attack, airlift, and combat support capability for operations in Grenada in 1983 (Operation Urgent Fury), Libya in 1986 (Operation El Dorado Canyon), and Panama in 1989 (Operation Just Cause).

Lessons learned in these operations were applied to its force structure and doctrine, and became the basis for successful air operations in the 1990s and after Sept. 11, 2001.

The development of satellite reconnaissance during the Cold War, the extensive use of both tactical and strategic aerial reconnaissance during numerous combat operations, and the nuclear war deterrent role of the Air Force resulted in the recognition of space as a possible combat arena.

The F-117 Nighthawk, the world’s first attack aircraft to employ stealth technology, was retired from the Air Force inventory in 2008. The aircraft made its first flight at the Tonopah Test Range, Nev., in June 1981. The F-117 took part in Operation Desert Storm, as well as operations in the former Yugoslavia.

An emphasis on “aerospace” operations and doctrine grew in the 1980s. Missile warning and space operations were combined to form Air Force Space Command in 1982.

In 1991, Operation Desert Storm provided emphasis for the command’s new focus on supporting combat operations.

The creation of the internet and the universality of computer technology as a basic war fighting tool resulted in the priority development of cyber warfare techniques and defenses by the Air Force.

Gulf War, Operation Desert Storm

Following Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in late 1990, President George H.W. Bush assembled a coalition to force the Iraqis out of Kuwait.

The U.S. Air Force provided the bulk of the Allied air power during the Gulf War in 1991, flying alongside aircraft of the U.S. Navy and the Royal Air Force.

The F-117 Nighthawk stealth fighter’s capabilities were shown on the first night of the air war when it was able to bomb central Baghdad and avoid the sophisticated Iraqi anti-aircraft defenses.

The Air Force, along with the U.S. Navy and the RAF, later patrolled the skies of northern and southern Iraq after the war to ensure that Iraq’s air defense capability could not be rebuilt.

Operation Provide Comfort, 1991-1996, and Operation Northern Watch, 1997-2003, patrolled no-fly zones north of the 36th parallel north; and Operation Southern Watch patrolled a no-fly zone south of the 33rd parallel north.

Troops of the U.S. Army’s XVIII Airborne Corps wait to board a C-130 Hercules transport aircraft of the 1630th Tactical Airlift Wing for a transit to Fort Bragg, N.C., following the liberation of Kuwait during Operation Desert Storm. Behind the troops is another C-130 Hercules aircraft.

In 1996, Operation Desert Strike and 1998 Operation Desert Fox, the Air Force bombed Saddam Hussein’s Iraq.

Air Expeditionary Force

Faced with declining budgets for personnel and resources in the late 1990s, the Air Force realized that it had to change the way it did business if it was to continue in business providing air power in support of America’s national and international interests.

In the mid-1990s, the Air Force was carrying out the “deny-flight” patrols of Operations Northern and Southern Watch over Iraq. These airborne patrols were tedious, boring and placed additional burdens on an Air Force that had been significantly downsized after the end of the Cold War and Operation Desert Storm.

As the mission continued into one of multi-year duration, the obvious drain on equipment and manpower forced the Air Force to reconsider how it was going to meet its future worldwide commitments.

The Air Expeditionary Force concept was developed that would mix Active-Duty, Reserve and Air National Guard into a combined force. Instead of entire permanent units deploying for years on end, units composed of “aviation packages” from several wings, including active-duty Air Force, the Air Force Reserve Command and the Air National Guard, would be married together to carry out the assigned deployment rotation.

In this way, the Air Force and its reserve components did not have to provide complete units of their own to meet the requirements placed before it by the Air Staff and the combatant commanders.

Unlike the overseas major commands already established, such as Pacific Air Force and U.S. Air Forces Europe, CENTAF (later AFCENT) would notconsist of permanently assigned units. Instead of the “Provisional” deployed units attached to the command during the 1991 (Persian) Gulf War, “Air Expeditionary” units would be the force projection components of CENTAF.

Air Expeditionary Force units are composed primarily of Air Combat Command or ACC gained components, but also components deployed from other major U.S.-based and overseas commands as necessary to meet mission requirements.

AEF organizations are defined as temporary in nature, organized to meet a specific mission or national commitment. As such, they are activated and inactivated as necessary and do not carry any official lineage or history.

Knowing that overseas basing was not something that could always be counted on due to the volatility of U.S. relations with host nations, the Air Force decided that keeping units fixed in static locations was no longer a viable option. Instead of using the Cold War model of a large number of permanent bases with units assigned, the Air Force modified its war plans to include the use of fewer, temporary bases that would be used by multiple AEF units rotating in for a finite amount of time, then inactivating afterwards.

Another not-to-be-forgotten benefit of the Air Expeditionary Force concept, at least for the reserve components — is that their members are all volunteers. When an AFRC or ANG unit is assigned to the AEF rotation cycle, it is the unit’s responsibility to obtain the needed personnel to fulfill the requirement. Other than units activated by presidential order, the utilization of ANG and AFRC personnel to support the AEF rotation cycles has always been accomplished on a completely voluntary basis.

In addition, the various Air Expeditionary Wings formed by the Air Force for the purpose of meeting the various deployment rotations allowed the deployment burden to remote combat areas of AFCENT be spread more evenly over the total force, while providing meaningful training opportunities for reserve component units that otherwise would not have had them.

Bosnia and Kosovo

The U.S. Air Force led NATO action in Bosnia with no-fly zones (Operation Deny Flight) 1993-96 and in 1995 with air strikes against the Bosnian Serbs (Operation Deliberate Force).

This was the first time that U.S. Air Force aircraft took part in military action as part of a NATO mission. The Air Force led the strike forces as the NATO air force (otherwise mainly composed of RAF and Luftwaffe aircraft) with the greatest capability to launch air strikes over a long period of time.

In 1999, the U.S. Air Force led NATO air strikes against Serbia during the Kosovo War (Operation Allied Force). NATO forces were later criticized for bombing civilian targets in Belgrade, including a strike on a civilian television station, and a later attack which destroyed the Chinese embassy.

Global War on Terror

On Sept. 11, 2001, the world changed.

Following the attacks, in 2001, the U.S. Air Force was deployed against the Taliban forces in Afghanistan.

Operating from Diego Garcia, B-52 Stratofortress and B-1 Lancer bombers attacked Taliban positions. The Air Force deployed daisy cutter bombs, dropped from C-130 Hercules cargo planes, for the first time since the Vietnam War. During this conflict, the Air Force opened up bases in Central Asia for the first time.

An F-16C Fighting Falcon fighter aircraft from the 388th Tactical Fighter Wing, Hill Air Force Base, Utah, is prepared for a strike against targets in Iraq and Kuwait during Operation Desert Storm.

The Air Force was deployed in the 2003 invasion of Iraq and, following the defeat of Saddam Hussein’s regime, the Air Force took over Baghdad International Airport as a base.

Operations in both Afghanistan and Iraq demonstrated the effective utility of Unmanned Air Vehicles, the most prominent of which was the MQ-1 Predator.

A total of 54 Air Force personnel died in the Iraq War.

By December 2011, all U.S. forces were removed from Iraq.

In March 2011, U.S. Air Force jets bombed military targets in Libya as part of the international effort to enforce a United Nations resolution that imposed no-fly zone over the country and protected its people from the civil war that occurred when its dictator, Muammar Gaddafi suppressed the protests calling for the end of his regime. Protests were inspired by the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt.

Modern Day

Today, the U.S. Air Force is the largest, most capable and most technologically advanced air force in the world, with about 5,778 manned aircraft in service, approximately 156 Unmanned Combat Air Vehicles, 2,130 Air-Launched Cruise Missiles, and 450 intercontinental ballistic missiles.

The U.S. Air Force has approximately 328,439 personnel on active duty, 74,000 in the Selected and Individual Ready Reserves, and 106,000 in the Air National Guard. In addition, the Air Force employs 168,900 civilian personnel including indirect hire of foreign nationals.

However, after two decades of failure to recapitalize its aircraft, the Air Force has its oldest and most outdated fleet ever. Tactical aircraft purchases were put off while fifth-generation jet fighters were facing delays, cost overruns and cutbacks and the programs to replace the 1950s bomber and tanker fleets have just been started over again after many aborted attempts.

As the U.S. Air Force enters a new chapter, the F-35 Lightning II is now operational, the Air Force and Boeing are testing a new air-refueling tanker, and Northrop Grumman has received a contract to begin development of the B-21 Raider long range strike bomber. And development and deployment of new and improved unmanned aerial vehicles continues.

Additionally, today’s airmen are the most educated and highly trained the Air Force has even seen.

It is safe to say that the future of the U.S. Air Force is in good hands.