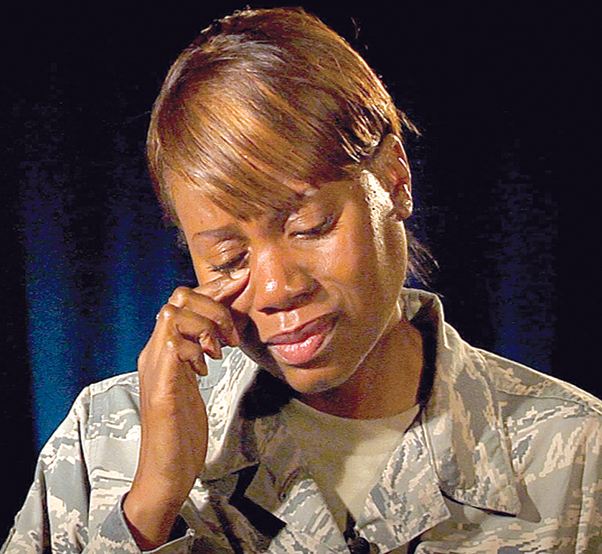

Master Sgt. Vickie Tippitt, a member of the 926th Force Support Squadron and the Nellis Air Force Base Yellow Ribbon representative, sheds a tear during an interview to discuss her rough childhood and how the Air Force saved her, at Nellis Air Force Base, Nev., Oct. 20, 2015. Tippitt, who plans on sharing her story with the base populace Jan 21. as part of a new Storytellers program, hopes to connect with other Airmen who might have gone through the same struggles through their childhood.

NELLIS AIR FORCE BASE, Nev. — The alarm rings. Yelling is heard from the nearby hallway. As footsteps get closer, Vickie Tippitt knows she is in a world of trouble.

Her grandmother bursts through the door. With a rope in hand, Tippitt feels the wrath of child abuse come down on her by her own flesh and blood.

That was the childhood that one Air Force Master Sergeant had to go through until she finally found her calling in the Air Force.

Tippitt, now a member of the 926th Force Support Squadron and the Nellis Air Force Base Yellow Ribbon representative, said life wasn’t always easy growing up in Fort Worth, Texas.

“I remember having a good childhood at three years old all the way until I was seven. Once I turned seven, that’s when a lot of things changed for me,” Tippitt said. “That’s when my mother and father decided to separate. There was a lot of fighting, and my dad was very, very abusive to my mother. Then we moved to Arlington, Texas, into an apartment where it was my mother, four siblings and me. That’s when everything was just really confusing.”

Tippitt’s mother worked every single day, and still works the same job she did when Tippitt was seven. With Tippitt’s mother working the night shift, Tippitt and her siblings were often alone, before her grandmother came for them.

“All of the sudden, I could remember being whisked away from school one day by my grandmother and when we left with her we never got to come back,” Tippitt said. “She took us to this house in Fort Worth, and all of a sudden we were in this house for at least a month or two where all of us kids were alone. We had no lights, no gas, there was nothing really. We had to eat lemon cake mix.”

With Tippitt’s grandmother never around, the house became a wreck.

“At that age, you do whatever you want. If there is no gas and no water, you are outside going to the bathroom, using the neighbor’s water. One time, my brother set the mattress on fire because he was upset,” Tippitt said. “More than anything, I remember my grandmother finally coming back to the house after being away for a while and she was very upset. She put us all in a row and beat the hell out of us with a very thick rope that they use to lasso horses or cows.”

After being beat by her grandmother, Tippitt and the rest of her siblings moved from place to place before settling in the housing projects.

“We moved to some apartments, and the abuse continued. Mean things were said and done. Then we moved from the apartments to the Butler housing projects,” Tippitt said. “It was a chaotic home. I will say that there were a lot of drugs, alcohol, a lot of partying, and drug addicts. There was always someone in the home.”

With the house always full of people, Tippitt was counted on to clean up and serve guests while they were there.

“When people came to the house, I always had to keep the house clean, wash the dishes, and basically be a servant to anyone that was there,” Tippitt said. “If it wasn’t done, I would get the hell beat out of me and also I wasn’t able to go to school. School for me was a great place to go.”

Tippitt and her sister were often times subjected to sexual passes made by the male guests.

“There were several nights where men would try to come into me and my sister’s room and they would try to talk us into being with them or touching them,” Tippitt said. “I’m blessed that I never got molested. It was like that from seven to 15 years old.”

When Tippitt was 15, she would sneak out of the house and see her mom with her sister so she could get out of the harsh environment that she lived in.

“I finally ran away when I was 15 years old. We piled our clothes into trash bags and threw them out of our window. When it was time to go to school, we were standing at the bus stop with our trash bags waiting to run away to our mom,” Tippitt said.

When Vickie Tippitt was a teenager, she worked as a lifeguard in the summer, and then on a whim, she decided to check out a U.S. Air Force recruiter’s office.

“I was a lifeguard and I was going for lunch one particular day, so I decided to go to the mall to go shopping and I went to a different area of the mall near the back where I noticed there were all these different recruiting agencies,” Tippitt said. “They had Navy, Army and then I saw Air Force, and I knew when summer time was over, I had no idea what I would be doing. So I decided to go into the Air Force recruiting office and as soon as I walked in I told the recruiter I wanted to join the Air Force.”

After joining the Air Force, Tippitt found out how her grandmother was able to take her and her siblings away from her mother.

“My grandmother called the welfare office and had informed them that my mother had died. She told them that she wanted full guardianship of all of us kids. They told her she needed to produce a death certificate,” Tippitt said. “At one point, she used to be a mortician and that fell into her profession. However, she wasn’t able to produce a certificate and called back saying that she thought she was dead because she was a drug addict. They believed her and she took full guardianship. My mother spent time in jail for it, and she never did drugs.”

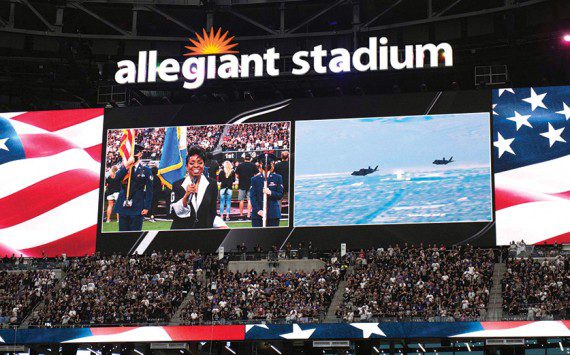

Tippitt, who plans on sharing her story with the base populace Jan 21. as part of a new Storytellers program for the base, hopes to connect with other Airmen who might have went through the same struggles.

“When airmen hear these stories, it’s going to transform lives,” 99th Air Base Wing Chaplain (Lt. Col.) Dwayne Jones said. “We are going to hear that there is hope, we can be resilient in difficult times. If life dealt you a bad hand, there is always an opportunity for a new beginning.”

Now that Tippitt has fully left her past behind, she looks back in astonishment.

“I never thought I would be smart enough or courageous enough to leave that type of environment,” Tippitt said. “Today, I don’t consider myself a victim, I just consider myself being able to take up for myself and able to take care of myself.”