Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder is a significant or extreme emotional or psychological response to a shocking, dangerous or traumatic event. It affects approximately seven percent of the United States population and nearly 12 to 18 percent of combat veterans deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan.

CREECH AIR FORCE BASE, Nev. — When every service member signs their name on the dotted line to become of a part of the military, they agree to follow orders and even go to war.

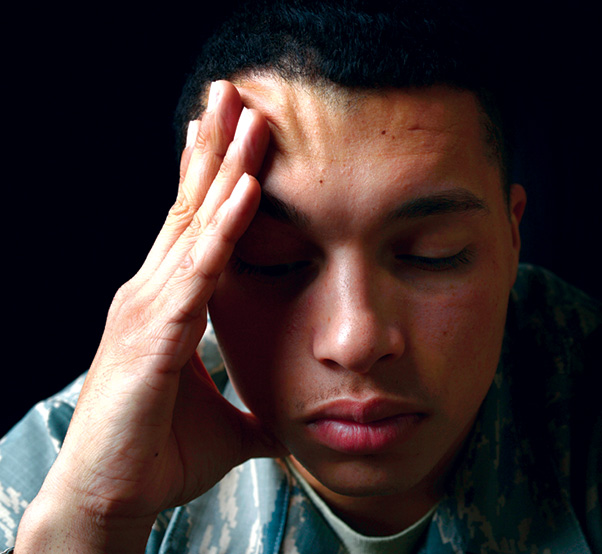

However, some military members come home with scars, not all of them visible.

For these men and women, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) can become an unwanted reality.

“PTSD is a significant or extreme emotional or psychological response to a shocking or dangerous or traumatic event,” said Maj Richard, 432nd Wing operational psychologist. “To be diagnosed, symptoms are identified that fall into four clusters and would have been experienced for at least one month.” In addition to these symptoms individuals experience significant impairment to their daily lives and routines which collectively result in the mental health disorder known as PTSD.

Symptom clusters can range from re-experiencing traumatic events, avoidance, arousal, and cognitive and emotional problems. Those suffering PTSD may have nightmares or flashbacks, may avoid places or things they used to do, may be more irritable, restless, have trouble sleeping and may even experience emotional numbness or shame.

While the events that cause these symptoms are often mistaken to be specific only to combat events, they can be also be a result of events such as firefights, natural disasters, witnessing a friend’s death or injury and more.

“For some combat veterans, they experience survivor’s guilt,” Richard said. “They wonder why they survived while their friends died and how they can enjoy their lives going forward.”

Trauma events are not limited to just military members. Every day distressing events such as traffic accidents, assaults, or injuries can result in PTSD.

“Research by The National Institute of Mental Health indicates the adult prevalence rate of PTSD is approximately 6.8 percent,” Richard said, “With 9.7 percent for women and 3.6 percent for men.” In other studies PTSD was identified in approx. 12-18 percent of combat veterans deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan.”

There are many myths surrounding PTSD in the military. A more recent myth is that remotely piloted aircraft aircrew are more susceptible to PTSD.

Richard went on to relay that during a 2015 USAF School of Aerospace Medicine survey, five percent of pilots and sensor operators within the MQ-1 Predator and MQ-9 Reaper community endorsed symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress. However, the mere presence of such symptoms does not automatically translate to PTSD, which would indicate life impairment, nor did the study relate symptoms to military or combat duties. The study inferred the probability of less incidence of PTSD when comparative to the civilian population and other military cohorts, as well as it highlighted the importance and relevance of trauma responses that may benefit from some form of support.

Despite the commonality of people experiencing a significant response to trauma in everyday life, it is not uncommon that people may not want to accept support for their experience.

“Sometimes people want to just do their jobs and say ‘I don’t want to be told I’m broken because I don’t see myself that way’. But if they do tell me that, how do I deal with that?” Richard said. “Some people won’t go to mental health because they don’t want to get labeled. They’re afraid of being treated differently.”

For military members, there’s been a stigma about going to mental health.

“For a lot of years there’s a stigma of mental health that if you go, something bad will happen like losing your firearm, not being able to fly or losing your clearance, but these are all myths,” Richard said.

Because of these myths, some service members may choose not to seek help.

“There is no good reason for not getting help. Less than two percent of people who go to mental health have career impacting decisions made,” Richard said. “Maybe they lost their firearm or flying status for a little bit but the individuals got it back them. It doesn’t get better on its own, it will only get worse.”

PTSD and post-traumatic stress symptoms can be treated and it’s important to seek help as soon as possible.

“Get treatment early,”Richard said. “Manage it, resolve it, go forward, and if something happens in the future, you’re better prepared to handle it.”

There are many treatments, but the most practiced by the DOD is prolonged exposure therapy, and cognitive processing therapy and certain types of medications. The first two treatments take approximately 12 weeks to complete.

Prolonged Exposure Therapy is the practice of mentally re-experiencing the traumatic event and engaging with it rather than avoiding it. This helps individuals to process the trauma and reduce distress. This is also known as fear extinction.

Cognitive Processing Therapy is a three-phase practice of educating and informing the patient about PTSD and their thoughts, helping patients develop skills to challenge their own thoughts, and finally helping the patient apply adaptive coping techniques.

The Cognitive Behavior Conjoint Therapy is a newer treatment which involves the patient’s family as a support system during the therapy.

PTSD is a problem that has affected the lives of many Americans, including service members. Often times the negative stigma associated with seeking professional mental health is daunting. Getting help early and staying close with family and friends could help individuals overcome the struggle of post-traumatic stress symptoms and decrease the risk of developing or exacerbating PTSD.

“Having a spouse, friend, or family member during initial therapy can give a better understanding of what to look out for and how to help the patient,” Richard said. “It’s important for the family to be patient and flexible. The member will have good days and bad days and it’s important for the family to be supportive both emotionally and by keeping them on the treatment path.”