“On Oct. 1, 2017, at 10:08 p.m., I was asleep in my bed like every Sunday before that,” said Maj. Charles Chesnut, a general surgeon assigned to the 99th Medical Group, Nellis Air Force Base, Nev.

“About an hour and a half later, I was awakened by the Air Combat Command emergency notification system: ‘Avoid downtown Las Vegas — active shooter on the strip.’”

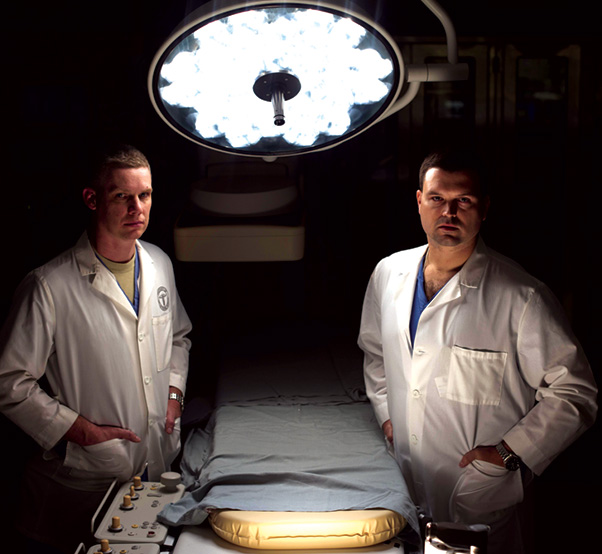

Chesnut, along with three general and three resident surgeons assigned to the 99th MDG, responded to the University Medical Center of Southern Nevada to help treat patients injured during the largest single shooter massacre in modern U.S. history.

“Within two hours after the incident, all the resuscitation bays were full and six patients were being operated on by trauma surgeons,” said Chesnut. “Everyone worked together taking care of these patients to do some good in the face of evil.

“We treated over 100 patients, ranging from surgical procedures to end of life care,” said Chesnut.

The Air Force and civilian surgeons worked hand-in-hand through the night to treat patients’ visible wounds in the operating rooms, while also addressing invisible wounds at the bedsides.

“We held their hands as they charged their cellphones, so they could reach out to family members, who feared for their lives,” said Chesnut.

After a few hours, time blurred as the second wave of injured patients arrived around 3 a.m. from smaller hospitals that no longer had the capacity to treat.

“The environment down there was controlled chaos, but the disaster response plan that the hospital had in place for a mass casualty worked,” said Chesnut. “At no point did I feel like our capacity was overwhelmed.”

As 7 a.m. approached, the influx of patients ended, and the UMC began to settle.

“Days like we experienced at UMC are the toughest ones, when you have multiple patients injured while multiple patients are continuing to come to the hospital,” said Col. Brandon Snook, Director of the Air Force SMART (Sustained Medical and Readiness Trained) Program at UMC, a partnership between the USAF and UMC. “Those are some of the toughest days, but also very rewarding. We all see a problem and do what we can to fix it to help out patients.”

“The acts of one person aren’t the acts of many,” said Chesnut. “That one man did terrible things to almost 600 people, but as we’ve seen in the days following, hundreds of people have done amazing things to recover.”