Even before the attack on Pearl Harbor, some military and Congressional leaders had considered creating a Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, which would provide women to fill office and clerical jobs in the Army, thus freeing up men for combat roles.

When after the Japanese attack Congress re-considered its stance on women in the military, it was more accommodating. Still, however, an acrimonious debate resulted in a compromise bill signed on May 14, 1942, which created a WAAC but did not grant its members military status.

In June, Oveta Culp Hobby, whom Army Chief of Staff Gen. Catlett Marshall had selected, put on the first WAAC uniform and became its first leader.

By November, the WAAC had already surpassed its initial recruiting goal of 25,000 women, and Secretary of War Henry L Stimson ordered the program expanded to the maximum size Congress had set: 150,000.

This number was difficult to reach, however, because of Director Hobby’s insistence on high recruiting standards, competition with the Navy’s program for women, and a general skepticism and even hostility many WAACs encountered from men within and outside the Army.

The program nevertheless continued to be a military success, and in the spring of 1943, the Army asked Congress to allow the conversion of the WAAC into the Regular Army. This change would equalize an array of benefits and protections that the WAACs, as auxiliaries, currently lacked. After much debate, Congress approved, and on July 3, 1943, the WAAC became the Women’s Army Corps, or WAC. Some WAACs did not want to continue as part of the Regular Army, and around 25 percent of them decided to leave the service.

Many women still continued to find the WAC an appealing career, especially when assigned to the AAF, where they were known informally as Air WACs. Most of the first recruits were assigned office duties, or worked to operate listening posts for the Aircraft and Warning Service, which monitored US borders for possible enemy attacks. At its peak in 1945, the Air WACs boasted over 32,000 women in more than 200 enlisted and 60 officer occupational specialties.

Eventually, 40 percent of all WACs went into the AAF, where they worked in an increasing variety of roles. By January 1945, only 50 percent of AAF WACs worked in the assignments traditionally seen as appropriate for women, such as stenography, typing, and filing. Instead, Air WACs served increasingly as weather observers, cryptographers, radio operators, aerial photograph analyzers, control tower operators, parachute riggers, maintenance specialists, and sheet metal workers . About 1,100 black women served in segregated units, as did smaller numbers of Japanese-American (50) and Puerto Rican (200) women. More than 7,000 Air WACs served overseas in every theater of operations, and three WACs received the Air Medal.

At the end of the war, V-J Day on Sept. 2, 1945, the WAC as a whole had 90,779 members.

Though many women and men in the Army looked forward to their demobilization, many other women also hoped that they could continue after the war. Some Army officers, such as Lt Gen Ira C. Eaker, then the Deputy Commander of the Army Air Forces, recommended WAC retention based on their good performance during the conflict, while other officers and public figures feared that retaining women in the military would weaken the nation’s moral fiber. In the end, both men and women rapidly demobilized, leaving WAC strength on Dec. 31, 1946, at less than 10,000.

Following the war, most Air WACs were discharged, and no WACs were transferred to the Air Force when it became a separate service in 1947. About 2,000 enlisted personnel and 177 officers continued to work in Air Force units, although they remained in the Army.

WACs at Bolling Field use a theodolite to obtain data on upper air flow of a balloon. (Courtesy photo)

After two years of debate and delay, Congress finally established an enduring place for women in the military with the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act of June 1948. This bill created the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) and Women in the Air Force (WAF), a corps of 300 officers and 4,000 enlisted women, none of whom could serve as pilots despite women’s past performance in the cockpit.

In June 1976, the U.S. Air Force began to accept women into the service on much the same conditions as it did men, including allowing admission to the United States Air Force Academy. The separate status of the WAF was then abolished, and women Airmen could then serve in an increasingly broad range of professional roles within the regular Air Force.

DON'T FORGET TO SUBSCRIBE

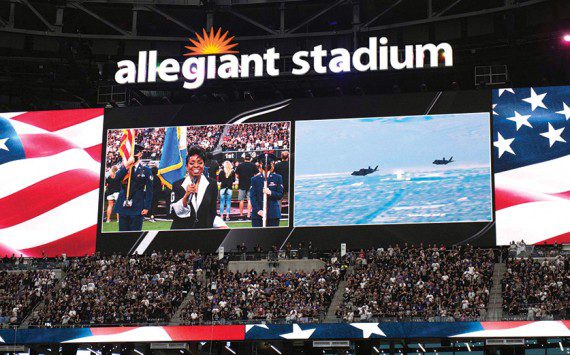

Get the latest news from Desert Lightning News at Nellis & Creech AFB