ROYAL AIR FORCE MILDENHALL, England (AFNS) — When 2nd Lt. John “Spike” Nasmyth climbed into his F-4 Phantom II on Sept. 4, 1966, to fly a combat mission over Vietnam, he never foresaw that he’d be blown out of the sky by a surface-to-air missile.

The last words he heard before his jet was transformed into a lump of crumpled, metal wreckage were from his “guy in back,” Ray Salzurulo, a pilot systems operator — “Hey, Spike — here comes another…”

Direct hit

As the missile struck, the first thing in Nasmyth’s mind was disbelief.

“As with all good fighter pilots, I thought I was invincible,” said the 74-year-old Vietnam veteran and former prisoner of war during a visit to Royal Air Force Mildenhall July 8. “I couldn’t believe that they’d got me. But then, as I realized I was falling toward the ground at an appalling rate, I said to myself, ‘Eject or die, Spike!’ It looked like a movie — I was tumbling toward the ground and it just looked like it was spiraling toward me at a hell of a rate. That’s what made me eject.”

In 1966, Nasmyth was assigned to the 555th Fighter Squadron, 8th Tactical Fighter Wing, at Ubon Air Force Base, Thailand, where he flew combat missions in support of the Vietnam War.

Crash landing

After what seemed like an eternity, his parachute opened and brought him down to Earth, somewhere north of Hanoi. Struggling to free himself from his canopy harness, Nasmyth realized he’d been injured during the ejection. A shard of metal had gouged through his arm and gone in just below the elbow, out the other side and straight into his leg.

“It was just like a piece of red, raw meat was coming out of my right arm,” said Nasmyth, as he showed off his forearm and the scars he still bears today.

Once on the ground, he was immediately surrounded by the North Vietnamese, some of whom started to beat him before hauling him away to collect their bounty. They took him to the infamous Hanoi Hilton — the first of several prison camps which would become his “home” for the next 2,355 days.

Unbreakable spirit

Nasmyth was subjected to constant torture and near starvation during the first three years. The guards would find any reason to humiliate him and try to break his spirit. Refusing to acknowledge that Nasmyth was a prisoner of war, they referred to him as a war criminal, and, as far as they were concerned, the Geneva Convention didn’t apply to war criminals.

After several months of solitary confinement, he was allowed to mix with the other “American air pirates,” as they were called by their captors. Together, the prisoners were held in a camp known as “the Zoo.”

Sunny side of life

Being reintegrated into the general population of the camp brought new challenges for Nasmyth. Primarily, this meant getting along with others and sharing a cell. An antagonistic relationship between cellmates could make long days and months even worse.

“I only had one I considered killing,” said Nasmyth, in a tongue-in-cheek way. “Luckily, I had great cellmates; my best one ever was a guy named Jim Piere, from Bessemer, Alabama. Nothing got him down; everything was a joke. I was with him for six months, and we laughed the entire time.”

Nasmyth’s positive outlook is what he said got him through dark times where others would have given up.

“I’m a perpetual optimist and always have been,” Nasmyth said. “I always see the light at the end of the tunnel. Most fighter pilots are optimists, because flying a fighter plane is damn dangerous. It’s nothing but a little tube full of fuel and bombs. So you don’t get worried about things going ‘boom.’

“Most fighter pilots figured they’d survive and get out — most of us did,” he continued. “The optimists survived, the pessimists died. Every guy I know who died was a pessimist. If you look at the dark side and think you’re probably not going to make it, you don’t.”

‘Remember — no ‘k”

The prisoners learned to communicate in the form of tapping on the walls and quickly passed messages around the camp in this manner. An entire communications network was built upon “the tap code.”

When he first entered the camp in solitary confinement, Spike had heard the tapping, but had no clue as to what it was. His fellow Americans taught him the secret code: “The alphabet has 25 letters, no ‘k’. Five lines of five letters, the first tap is for the line. The second tap is the letter in the line. Remember, no ‘k;’ use ‘c’ for ‘k.’

“I had nothing but time on my hands, so I practiced,” he said. “I could do it so well and would send messages fast and receive them first; it kept me busy and in the know.”

The code helped keep the POWs safe and sane, and enabled them to share which lies they would tell their torturers. If they all said the same thing, then there was more chance of being believed.

All the while, the prisoners were on the lookout for the Vietnamese guards. If caught communicating, they were subjected to severe punishment. One prisoner would be down on his hands and knees looking through the gap under the door, keeping watch for the boots of their captors.

“I don’t think they ever figured out the extent of our communications,” said Nasmyth, as he laughed. “They’d have probably just cut our heads off. They just didn’t have a dream that we were as clever as we were. We could get a message through the 14 cells in the Zoo in three days. Even though it was caveman-primitive how we did it, we did it pretty cleverly.”

Free at last

As B-52 Stratofortresses attacked Hanoi during Operation Linebacker II from Dec. 18-29, 1972, Nasmyth recalled how the men at the Zoo endured a very violent two weeks that ended as quickly as they had begun.

“Then everything stopped. The Paris peace talks were happening and after we bombed Hanoi, the Vietnamese decided they’d had enough of that, so they signed the Paris Peace Accords Jan. 3, 1973,” he said.

One of the stipulations of the accord was that it had to be read to all the prisoners, so they were marched outside the Hanoi Hilton, where someone read the whole thing to them — in Vietnamese.

“None of us understood two words of it and it took them about an hour to read,” he recalled, adding that an interpreter eventually read it in English.

Approximately 300 men were released. For most, this was the first chance they’d had to see each other. Inside the prison, they’d never been allowed to all be together.

“My big worry the whole time was that I’d wake up from a dream. Even the day I was released, I kept poking myself, saying ‘don’t wake up, man.'” Nasmyth said. “When I was on that American plane — a C-141 Starlifter — and flew out of there, I was still thinking it was a dream. But it wasn’t.”

From past to present

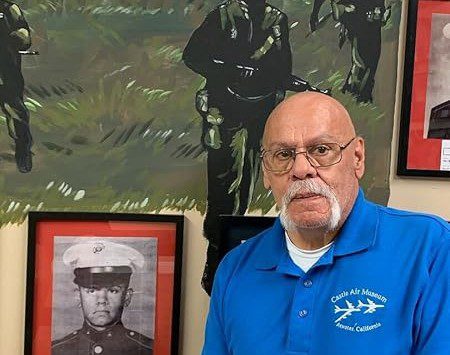

As the Vietnam veteran arrived at RAF Mildenhall on his way to talk to Airmen July 8, he saw KC-135 Stratotankers lined up on the flightline and reminisced about the memories they brought back.

A KC-135 was the last aircraft he saw before getting hit by the missile. It had just refueled his F-4, and he was full of praise for them.

“It was exhilarating and amazing to see them (on RAF Mildenhall). I thought, ‘my God — how old are they?'” Nasmyth said.

“We loved the tankers, because they saved our bacon,” he recalled. “They would deviate (from their route) and come north to get us if we were really short on fuel. They did it regularly, and I’m sure it was against orders, but they just did it. They were good guys.”

Hearing war stories from the past aids in keeping history alive and can help give Airmen of today a clearer picture of the struggles of those who served before them.

“Heritage is important to the 100th Air Refueling Wing and it should be for every Airman,” said Col. Thomas D. Torkelson, the 100th ARW commander. “To hear such incredible stories of service and sacrifice from a true hero of the Vietnam era is an amazing honor. Spike Nasmyth and his fellow POWs are an inspiration that motivates each of us to give a little more every day.”